REPRESENTATIVE

AND LEADING

MEN OF THE PACIFIC

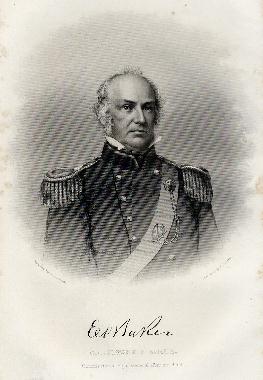

EDWARD

DICKINSON BAKER.

By HON. EDWARD STANLY.*

* For explanatory note, see Preface.

EDWARD DICKINSON BAKER was born in London, in 1811. His parents emigrated to the United States, and came to Philadelphia in 1816. They were highly respectable persons, of energy, good sense, and accomplished education. Upon the arrival of his parents in Philadelphia they taught school for a few years, successfully, at a time when that city was probably the most renowned of any in the Union for the excellence of its institutions of learning, and the ability of its distinguished citizens. His early lessons of religion were interwoven by his excellent parents with classical lore, and his taste bent to the purest models, and his precocious genius gratified in its thirst for books. His father had heard and read of our great government, founded by Washington and his compatriots, and regarded it as the noblest work of human wisdom and virtue, the most munificent spectacle of human happiness ever presented to the vision of man. The old man had seen sparks of irrepressible genius in his darling boy, and sought a theatre, upon which, without resting ingloriously under the shadow of a titled name, without “the boast of heraldry,” his son could make his mark upon the page of history. To the enduring honor of the old man, be it remembered, that notwithstanding his devotion to learning, he taught his children that labor was honorable; and for awhile our lamented hero worked at the trade of a cabinet-maker. But though to work as St. Paul did with his own hands is honorable among all men, yet the Almighty has given men different gifts. Baker’s genius could not be cramped by the persistent continuance of an occupation in which he could attain the highest excellence in a few years. To chain such a mind as he had to any such occupation, would be as idle as to attempt to persuade the bird of Jove to quit towering “in his pride of place,” and soaring aloft above the clouds, and adopt the habits of our useful domestic fowls. It could not be. It was the “Divinity that stirred within him,” and whispered that he was born to illustrate great principles by his mental efforts, and to die gloriously, as he did die, in the noblest struggle that ever animated the soul of a patriot-hero.

I can imagine that

sensible father holding the hand of his hope and joy as he walked through the

streets of the patriotic Quaker city. Here he showed him the house where

Washington dwelt, and the church in which the August father of his country

knelt in worship before the Lord of lords and King of kings. Here he visited

Independence Hall. Here he took him to the grave of Franklin, and in answer to

the inquiries of childish curiosity, he would say: “Washington, my son, was a

great and good man, honored by the brave and good throughout the civilized

work; he served his country faithfully through a long and bloody war, and

founded her, amid unexampled difficulties, a great and glorious Union, whose

laws insure protection to the honest foreigner and welcome him to an equal

participation in its rewards and honors. He earned the title, nobler far than

that of King or Emperor—

the Father of his Country. Study his precepts and venerate his character.

Benjamin Franklin was poor in early life, worked with his own hands, and by

industrious, and was honored by his fellow citizens and earned immortality. He,

like Washington and Franklin, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

These illustrious men, with their patriotic brethren from the icebound region

of the distant North, and the sunny clime of the South, pledged their lives,

fortunes and sacred honor to the achievement of Independence. Remember their

example— be true to that

country which they honored, which honored them, and may honor you, if you will.

This immortal struggle was one in which patriots of all the States

participated. At the battle of Germantown, Nash, from North Carolina, that

State the first to declare her Independence, (then peopled by thousands, as now

by tens of thousands, of good men and true,) here fell a martyr in the cause of

Freedom. On the other side of this majestic river—

the Delaware, which Washington crossed, disregarding the terrible inclemencies of a northern winter — on the other side, is the State of New Jersey, every

foot of whose soil is a soldier’s sepulcher. There Mercer of Virginia fell,

another martyr to Freedom’s cause. Be true to the memory of these men. You are

not by birth, but by choice can be, a fellow-citizen of this heaven blessed

Union. The prayers and hopes of your father and mother are that you will prove

true to this, now your country, to its institutions, to the cause of Freedom.”

This early teaching made a deep and

lasting impression on the heart and mind of the patriot-soldier. These early

lessons seem ever to have been the pillar of fire that guided his course in his

public career. When Col. Baker was still a boy, his father died in

Philadelphia. In 1828 he left that city, and seeking a home in the great West,

he went to Carrolton, Illinois, where he borrowed books and commenced the study

of law. May I say, without intruding in the holy precincts of family sorrow, he

went attended by a mother’s prayers and counsels. That mother still survives,

at the advanced age of 82 years, (1861). She is as remarkable now for the

sprightliness and vigor of her intellect, as she was in earlier life for her

accomplishments and rare endowments. Venerable woman !

While you reverse

our nature’s kindlier doom,

Pour

forth a mother’s sorrow on his tomb.

Millions of patriot hearts sympathise in your sorrow. Look for comfort in Him who alone can give it— who “doeth all things well.” May this calamity, while it “loosens another one of the bonds that bind you to the earth, divest the common fate of one more of its terrors, and create through the hope of re-union another aspiration for a better life beyond the grave.”

In 1832 he was a Major in what is known as the Black Hawk war.

By the diligent exertion of his extraordinary abilities, he soon attained a high rank in his profession— and this is no slight praise, for there were “giants in the land in those days.” Hardin, Douglas, Lincoln and Logan were his rivals and friends, and acknowledged his prowess. For ten years consecutively he was a member of the Legislature of the State of Illinois. In December, 1845, he entered the House of Representatives from the Springfield District in Illinois, a member of the 29th Congress. During this Congress, war existed with Mexico, and Baker left his place in the House, went to Illinois and raised the 4th Regiment organized in that State. He went with his regiment to the deadly banks of the Rio Grande, and entered the command of Gen. Taylor. In December, 1846, he returned from Mexico on urgent public business, and in the House of Representatives, delivered a speech remarkable for its force and intense patriotic feeling, which subdued partizan opposition and produced the fruits he desired, of additional appropriation for the comfort of the soldiers in the field. After this visit to the seat of Government he resigned his seat in Congress and returned to Vera Cruz, where he participated in the capture of the Castle of San Juan de Ulloa. Very soon afterwards he was at the battle of Cerro Gordo, where the gallant Gen. Shields was wounded severely, and Baker, having charge of the attacking column, took the command. History has told us the story of the good conduct of the Colonel who commanded the 4th Illinois Regiment, in that terrible but glorious day. After the war was ended, he returned to Illinois, and was honored by that State with a sword, in grateful recognition of his valuable services.

In 1849, while a resident of what was called the Sangamon or Springfield District, he was urged by his party friends to come to the Galena District, then strongly, and to any other person but Baker, overwhelmingly Democratic. In any other man had attempted such an enterprise, he would have been regarded as a Don Quixote. But he was always self-reliant. He had, if not all the ambition, the courage and genius of Julius Cæsar. He commenced there to advocate those principles to which through his life he had been attached, with unfaltering devotion. He went with the sling of Freedom and the pebble of Truth, and the giant Democracy fell before him. He served in the 31st Congress as a member from the Galena District. He was not a candidate again, and his voice not being heard, the Galena District was again decidedly Democratic.

In 1851, his fervid spirit, always seeking some difficult and hazardous exploit, induced him to embark in the enterprise of superintending the construction of the Panama Railroad. Here he managed a large body of men, and here he was reveling in the belief that he was opening a way to a land of wines and fig-trees, of pomegranates, a land of oil, olive and honey— opening the road for his countrymen in all parts of the Union, to a land forever consecrated to freedom. In that pestiferous climate, in “those poisonous fields with rank luxuriance crowned,” under

Those blazing suns that dart a downward ray,

And

fiercely shed intolerable day,

he was comforting his soul with the assurance that he was removing obstructions from the paths of free labor, that here, on this our blessed shore, it might have its proudest resting-place. Nothing but a strong constitution strengthened by the most exemplary temperance, a “frame of adamant, a soul of fire,” and an indomitable will sustained him under the effects of the Panama fever, which troubled him for several years.

In June, 1852, he arrived in California. Here he soon attained a high rank in the profession of law. Many pages of this volume might be filled in recounting his many triumphs among eminent men at the bar. The country well knows how pre-eminently great he was in cases of life and death— how irresistible he was, when he entranced juries by the magic of his eloquence, and deprived men of their reason as he overwhelmed them in admiration of his transcendent genius. By universal consent he was regarded as having no rival in this branch of his profession. It would be a grateful task to me, and a most agreeable one, to dwell upon the beauties of many of his published speeches. Who but Baker could draw such houses in old Music Hall, as Webster alone could summon in Faneuil Hall? Who could call alike the student and the mechanic to hear him discourse on advantages of free labor and the duty of government to protect and encourage it? Who could dim the eye of beauty with a tear of sympathy and soften the heart of the miser in one and the same effort, while he pleaded the cause of benevolence and heavenly charity? Who like him could call the miner from digging gold, the farmer from his plow, the man of business from his work, while he talked as one inspired of the thousand blessings of our Union, and the greatness that awaited us in the future? To those who have thus heard him, how “stale, flat and unprofitable” must be the effort of any other! How often, when we have thus heard him, with a heart overflowing with patriotism, and an eye of fire, when he spoke of the inestimable value of our Constitution and Union, of our mission among the nations of the earth, when he seemed to “stoop to touch the loftiest thought” which other men would toil laboriously to reach, have we thought he appeared to be the very personification of the apostrophe of the great poet of nature to man: “How noble in reason, how infinite in faculties; in form and moving, how express and admirable; in apprehension, how like a god!”

He remained in California until February, 1860. Then he attempted and achieved what no other man but E. D. BAKER could have performed. He had for years scattered the seeds which he saw had at last promised to bring forth good fruit in California, when he determined to perform in Oregon, upon a larger scale, what he had done in Illinois. Many who heard of his intentions, prophesied he was going on a “sleeveless errand,” that he was a Quixotic Hotspur who imagined “it were an easy leap to pluck bright honor from the pale-faced moon.” But he went to Oregon. He drew crowds to hear him. In a little more than six months he appeared again among us, on his way to Washington City, Senator from Oregon! It was, in evil conflict, like that of Julius Cæsar in arms over Pharnaces, as described by himself, Veni, vidi, vici— If “Peace hath her victories as well as War,” where is the conqueror whose laurels will not pale their ineffectual glories, before those of Baker? His success in the Galena District of Illinois and in Oregon is unequaled by anything that ever occurred in the history of our country.

He took his seat in

the Senate in December, 1860. Much was expected of him; he did not disappoint

the hopes of his friends. In January, 1861, in answer to the talented Benjamin,

the skillful and accomplished orator of “high exploit” in the Senate— “a fairer person lost not heaven”—

he made a speech celebrated for strength of argument, logical power and

majestic eloquence, which would have honored the Senate in the days of Webster,

Clay and Crittenden. He was beyond comparison the foremost man in debate in

that illustrious body, the Senate of the United States. It might have been

expected, as it was ardently hoped by his countrymen, that here he would

remain, and enjoy the fruits of an honorable ambition. But no; it was ordered

otherwise by fate. The ruling passion of his soul, that “made his ambition

virtue”— an unconquerable wish to serve and save his comfort. In his own

glowing words in the House of Representatives, in 1850, “I have bared my bosom

to the battles on the Northwestern frontier in my youth, and on the

Southwestern frontier in my manhood; and if the time should come when disunion

rules the hour, and discord is to reign supreme, I shall again be ready to give

the best blood in my veins to my country’s cause.”

The time had come, and he was ready

to do at the cannon’s mouth what he had professed in the halls of Congress. His

noble soul was on the side of his country in the dreadful contest brought about

by desperate and wicked ambition. His voice in the Senate and in the public

assemblies stirred the hearts of his countrymen to rally in support of the best

Government over seen by man. After the adjournment of Congress he attended a

public meeting in New York, in April, 1861, probably the largest ever held in

our country, and there, amid the learned and able men of that great city, he

stimulated the public mind and aroused his countrymen to renewed efforts in

behalf of our Union. It was there he spoke by the side of the lion-hearted, the

patriotic Dickinson— himself remarkable for strength of intellect and great

power of oratory— who at a speech in Brooklyn, New York, thus speaks of our

friend:

Alas, poor Baker! He was swifter than an eagle! He was

stronger than a lion! And the very soul of bravery and manly daring. He spoke

by my side at the great Union Square meeting in April, and his words of fiery

and patriotic eloquence yet ring upon my ear. And has that noble heart ceased

to throb— that pulse to play? Has that beaming eye been closed

in death? Has that tongue of eloquence silenced for ever? Yes, but he has died

in the cause of humanity—

“Whether

on the scaffold high,

Or in the army’s van,

The

fittest place for man to die

Is where he dies for man!

He raised a regiment and led them on in their country’s cause. It is not necessary now to discuss why the result of the battle of Edward’s Ferry was not different. To Baker’s fame it is all right. He fell in the cause of human liberty, in defense of the Union, in defense of his country. He fell with his “back to the field, his face to the foe,” and long as Liberty has a votary on earth, as long as the name of Washington is revered among men, and his principles cherished by his countrymen, so long will the name of Baker be remembered with gratitude and admiration.

No man who knew Baker, can doubt the sincerity and noble disinterestedness of his attachment to his political principles. In Illinois, in California, against overwhelming numbers, unseduced by the syren song promising promotion, he kept on the even tenor of his way. As statesman, he was never suspected in the days of highest party excitement, of trimming his sails to catch the breeze of popular applause. He did not purpose to embark with his friends on the “smooth surface of a summer sea,” and leave them when the winds whistled and the billows roared. He was

Constant as the Northern Star,

Of

whose true, fixed and resting quality

There

is no fellow in the firmament.

In political contests, when armed with the consciousness of being right, as at the cannon’s mouth, he never feared to encounter any adversary, or ever thought of consequences to himself. He went into political contests as he did to the field of battle, where mortal engines “immortal Jove’s dread clamors counterfeit.”

On the morning of the fatal 21st of October, 1861, when he crossed the Potomac, he went to perform his duty to the “whole country, of which he was a devoted and affectionate son.” He thought he was right, and in the path of duty; and I can imagine as he stood on the banks of the Potomac, whose rushing waters red with patriotic blood, were in a few hours to dash their moaning waves on Mount Vernon’s shore, with a full knowledge of the danger of death before him, he had in his mind the noble thoughts to which he gave utterance in the Senate on the 2d of January previous. “Right and duty are always majestic ideas. They march an invisible guard in the van of all true progress; they animate the loftiest spirit in the public assemblies; they nerve the arm of the warrior; they kindle the soul of the statesman and the imagination of the poet; they sweeten every reward; they console every defeat. Sir, they are of themselves an indissoluble chain which binds feeble, erring humanity to the eternal throne of God.”

In private life he was most amiable and affectionate.

I am indebted to the Rev. Thomas H. Pearne of Portland, Oregon, who thus speaks of an incident which illustrates the strength of his filial affection and duty. After his election as Senator, he addressed a letter to his mother:

It was the first he was to send being the Senatorial

frank. Who so fitting a recipient of that first letter as that aged mother? On

the way to the post-office with the letter in hand, conversing with a friend,

he remarked with fond pride, that his mother, then more than 80 years of age,

was a woman of strong, cultivated mind; that she had often taken down his

speeches in short-hand, which she wrote with elegance and rapidity; that she

was a beautiful writer, and that she still retained in vigor her mental

faculties. As the son was transmitting this evidence of his success to his

mother, and recounting her virtues and excellencies,

his eyes filled with tears, which coursed their way down his cheeks. In itself

the incident is trivial, yet it illustrates two things— the influence of that strongminded,

intelligent mother in training her son for greatness and usefulness, and the

generous tide of sympathy which beats in his manly heart.

He has as much unworldliness as Goldsmith; no love of filthy lucre ever found a resting-place in his heart. For years I have known him well, and part of the time was associated with him in business, and I never heard a profane word or irreverent expression from his lips. He never uttered or wrote a line that could impair the celestial comfort of a Christian’s hope. As a man, he was possessed of that most excellent gift, charity, towards all who differed with him; he never indulged in bitterness of speech towards political opponents, nor toward those who had done him personal wrong. I have never known a man in public life whose heart more abounded in generous philanthropy for all mankind. He exhibited this feeling at the bar, when he was conscious of his superiority over a younger or feebler adversary. He would have manifested the same generosity had he been victorious in the last battle of his life, and deserved the eulogium pronounced by him on Gen. Taylor: “Nor, sir, can we forget that in the flush of victory, the gentle heart stayed the bold hand, while the conquering soldier offered sacrifice on the altar of pity, amid all the exultation of triumph.”

He had talents that only needed cultivation to have insured him distinction, as a poet.

The following poem is given as an illustration of his poetical powers. It was sent from Washington City to the Philadelphia Press, (shortly after Col. Baker’s death,) by Col. Forney, with these comments.

Poem by Col. Baker.

“In my comments upon the lamented Colonel Baker I

stated that, in addition to his many other intellectual gifts, he was a fine

poet— a remark that was received by many with surprise. I

am permitted to publish one of his fugitive pieces, written by him twelve years

ago, and now in possession of an intimate friend in this city. Observe how the

last verse applies to his fate:”

TO A WAVE.

Dost thou seek a star with thy swelling crest,

O

wave, that leavest thy mother’s breast?

Dost

thou leap from the prisoned depths below

In scorn of their calm and constant flow?

Or

art thou seeking some distant land

To die in murmurs upon the strand?

Hast

thou tales to tell of pearl-lit deep,

Where

the wave-whelmed mariner rocks in sleep?

Canst

thou speak of navies that sunk in pride

Ere

the roll of their thunder in echo died?

What

trophies, what banners, are floating free

In the shadowy depths of that silent sea?

It

were vain to ask, as thou rollest afar,

Of

banner, or mariner, ship or star;

It

were vain to seek in thy stormy face

Some tale of the sorrowful past to trace.

Thou

art swelling high, thou art flashing free,

How

vain are the questions we ask of thee !

I

too am a wave on a stormy sea;

I

too am a wanderer, driven like thee;

I

too am seeking a distant land

To be lost and gone ere I reach the strand.

For

the land I seek is a waveless shore

And they who once reach it shall

wander no more.

It has fallen to the lot of few men to be distinguished at the bar, in popular assemblies, in the Senate, and in the tented field. Viewed in this light, Baker’s fame is the “tall cliff whose awful form” overshadows other men of his day. The practice of the law sharpens the intellect, but narrows its power of comprehension. It had no unfavorable influence on his genius. The great Erskine, unrivaled in his day in the forum, disappointed the hopes of all when he sat in Parliament. But Baker was an Erskine at the bar and a Chatham in the Senate. The magnificent Burke, whose splendid diction grows better by time, had no power to stir men’s blood as Baker had. Excepting our own Webster, no man of modern times has been so successful as Baker in the forum, in the Senate, and before popular assemblies. I have already referred to his surprising power in addressing audiences of literary or benevolent character. Which of us that heard or read his speech on the occasion of celebrating the laying of the Atlantic cable, in 1858, can ever forget his beautiful apostrophe to science?—

On Science, thou thought-clad leader of the company of

pure and great souls that toil for their race and love their kind! Measurer of

the depths of earth and the recesses of heaven! Apostle of civilization,

hand-maid of religion, teacher of human equality and human right, perpetual

witness for the Divine wisdom, be ever, as now, the

great minister of peace! Let thy starry brow and benign front still gleam in

the van of progress, brighter than the sword of the conqueror, and welcome as

the light of heaven.

Who can forget his reference on the same occasion to the magnificent comet, then kindling the admiration of all beholders in its pathway of celestial glory?—

“But even while we assemble to mark the deed and

rejoice at its completion, the Almighty, as if to impress us with our weakness

when compared with his power, has set a new signal of his reign in heaven. If

to-night, fellow-citizens, you will look out from the glare of your illuminated

city into the northwestern heavens, you will perceive low down on the edge of

the horizon a bright stranger pursuing its path across the sky. Amid the starry

hosts that keep their watch, it shines attended by a brighter pomp and followed

by a broader train. No living man has gazed upon its splendors before. No

watchful votary of science has traced its course for nearly ten generations. It

is more than 300 years since its approach was visible from our planet. When

last it came it startled an Emperor on his throne, and while the superstition

of his age taught him to perceive in its presence a herald and a doom, his

pride saw in its flaming course and fiery train the announcement that his own

light was about to be extinguished. In common with the lowest of his subjects,

he read omens of destruction in the baleful heavens, and prepared himself for a

fate which alike awaits the mightiest and the meanest. Thanks to the present

condition of scientific knowledge, we read the heavens with a far clearer

perception. We see in the predicted return of the rushing, blazing, comet

through the sky, the march of a heavenly messenger along its appointed way and

around its predestined orbit. For 300 years he has traveled amid the regions of

infinite space. “Lone, wandering, but not lost,” he has left behind him shining

suns, blazing stars and gleaming constellations, now nearer the eternal throne,

and again on the confines of the universe— he

returns with visage radiant and benign; he returns with unimpeded march and

unobstructed way; he returns, the majestic, swift electric telegraph of the

Almighty, bearing upon his flaming front the tidings that throughout the

universe there is still peace and order; that amid the immeasurable dominions

of the Great King, His rule is still perfect; that suns and stars and systems

tread their endless circle and obey the eternal law.

Are not these thoughts rays of immortality which cast a bright halo around the fame of Baker? He had errors — what mortal has not?— he was conscious of them, and repented of them in sackcloth and ashes. But who can think of the early career of this foreign-born boy, deprived by Almighty dispensation of a father’s care when a child of tender years; of his noble struggle against poverty; of his wonderful acquirements while working with his own hands; of his extraordinary attainments under the most depressing circumstances on a western frontier; of his great virtues in the domestic relations of life; of his gentle and charitable heart; of his patriotic soul devoted to his whole country, full of fiery zeal in the cause of liberty, yet untainted by the poison of fanaticism which corrupts the heart and clouds the mind; above all, of his steady, unfaltering devotion to his country, in peace and in war; of his patriotic life and glorious death— who can think of these, and refuse to say with the friend now attempting with tremulous diffidence to weave a modest garland around his brow, in doing these fair rites of tenderness—

Adieu, and take thy praise with thee to Heaven!

Let

thy errors sleep with thee in the grave

But not remembered in thy epitaph !

A few weeks after his election to the United States Senate, in 1860, Gen. Baker, while en route to Washington, addressed a very large mass meeting in San Francico, convened under the auspices of the Republican State Central Committee. His speech on this occasion was regarded by very many of his admirers as the greatest effort of his life, although delivered without preparation. It was reported in full, and extensively circulated as a campaign document. Near the close of the speech occurred this impassioned tribute to Freedom:

“Here, then, long years ago, I took my stand by

Freedom, and where in youth my feet were planted, there my manhood and my age

shall march. And, for one, I am not ashamed of Freedom. I know her power; I

rejoice in her majesty; I walk beneath her banner; I glory in her strength. I

have seen her again and again struck down on a hundred chosen fields of battle.

I have seen her friends fly from her. I have seen her foes gather around her. I

have seen them bind her to the stake. I have seen them give her ashes to the

wind, regathering them again, that they might scatter

them yet more widely. But when they turned to exult, I have seen her again meet

them, face to face, clad in complete

steel, and brandishing in her strong right hand a flaming sword, red with

insufferable light. And, therefore, I take courage. The people gather around her

once more. The Genius of America will at last lead her sons to Freedom.”

We honor him

especially for the self-immolating spirit which led him, like Curtius, to plunge in the gulf of hope of saving his

country. He was not impelled by any dream of wild ambition. Not being born in

the Atlantic States, he could not be President. He had attained the highest

station, in his opinion, on earth; a station, as he said, “more exalted than

that of a Roman Senator, Consul, Proconsul or Emperor.” He had obtained the position

of the first debater in the Senate. His friend with

whom he had played in childhood, “his own familiar friend” with whom he had

taken sweet counsel, had become President of the United States. That friend

still loved him and rejoiced at this success. He could have passed an easy and

luxurious life on the primrose path of Senatorial dignity and influence. But

his country was in danger—

he took no thought of himself.

He “loved the name of honor more than he feared death.” I honor his memory especially that notwithstanding his life-long zeal in the cause of liberty, he was true to “the Constitution and all its compromises,” as he proclaimed again and again in his public addresses. He was animated by no sectional hostility, but regarded our Union “as less a work of human prudence than of Providential interposition.” In the spirit of a disciple of Washington, as a friend of Webster and Clay, he said:

“Let the laws be maintained and the Union preserved, at

whatever cost. By whatever constitutional process, though whatever of darkness

or danger there may be, let us proceed in the broad luminous path of duty, till

danger’s troubled night be passed and the star of peace returns.”

At the Union Mass Meeting in New York City, May 20th, 1861, Gen. Baker thus concluded a speech of great eloquence and power:

And if, from the far Pacific, a voice feebler than the

feeblest murmur upon its shore may be heard to give you courage and hope in the

contest, that voice is yours to-day. And if a man whose hair is gray, who is

well nigh worn out in the battle and toil of life, may pledge himself on such

an occasion, and in such an audience, let me say, as my last word, that when

amid sheeted fire and flame, I saw and led the hosts of New York as they

charged in contest upon a foreign soil for the honor of your flag; so again, if

Providence shall will it, this feeble hand shall draw a sword never yet

dishonored— not to fight for distant honor in a foreign land, but

to fight for country, for home, for law, for government, for constitution, for

right, for freedom, for humanity, and in the hope that the banner of my country

may advance, and wheresoever that banner waves, there

glory may pursue and freedom be established.

It would be unjust to his memory and to his countrymen to whom his memory will ever be dear, to omit to speak of his funeral oration over the dead body of a Senator from California, who died “tangled in the meshes of the code of honor.” I have read no effort of that character, called out by such an event, so admirable, so touching, so worthy the sweet eloquence of Baker. That one effort should crown him with immortality. Baker was a brave man. He has proved it often. He had, as an honorable colleague said in the House of Representatives— “in the battles of his country carved the evidence of his devotion to his government,” and gave there proof of his courage. He proved it on the bloody field of Cerro Gordo, when he was praised by the greatest of living soldiers for his fine behavior and success. He has proved it by his death. Yet he knew that dueling was a sin. He knew it deserved reprobation and was unhallowed by any or all of the illustrious names who had yielded to its requirements under the tyranny of a barbarous public opinion. He gave his unqualified condemnation to a code which offers “to personal vindictiveness a life due only to a country, a family and to God.” Broderick had many good qualities that excited Baker’s admiration. Both were self-made men; both had risen from poverty to the highest position. Let Baker’s denunciation of this unchristian, barbarous code be remembered to his undying honor:

To-day I renew my protest; to-day I utter yours. The

code of honor is a delusion and a snare. It palters

the hope of a true courage and binds it at the feet of crafty and cruel skill.

It surrounds its victim with the pomp and grace of the procession but leaves

him bleeding on the altar. It substitutes cold, and

deliberate preparation for courageous and manly impulse, and arms the one to

disarm the other. It may prevent fraud between practiced duelists— who should be forever without its pale— but it makes the mere “trick of the weapon” superior

to the noblest cause and the truest courage. Its picture of equality is a lie.

It is equal in all the form, it is unjust in all the

substance. The habitué of arms, the early training, the frontier life, the

bloody war, the sectional custom, the life of leisure, all these are advantages

which no negotiations can neutralize and no courage can overcome.

There was a moral courage and sublimity in it that has a fadeless lustre, reflected by his glorious death. Not far from each other—

Where Ocean tells its rushing waves

To

murmur dirges round their waves—

these two distinguished men will repose in Lone Mountain cemetery until the trump of the Archangel shall sound and “summon this mortal to put on immortality.” Let their monuments arise to meet the eye of the ocean-worn exile as he comes near this haven of rest. Let them tell the traveler, as the landscape fades from his sight on leaving our gorgeous land, “the paths of glory lead but to the grave.” Let parents of unnumbered generations encourage their children to love that country for which Baker died— to cherish our Government and its institutions, which can thus advance the humblest of her sons. There let them rest, honored for their virtues, respected for their public services, mourned by thousands of all nations now present who will unite with us in saying:

How sleep the bravo who sink

to rest,

By

all their country’s wishes blest!

When

Spring, with dewy fingers cold,

Returns

to deck their hallowed mould,

She

there shall dress a sweeter sod

Than

Fancy’s feet have ever trod.

By

fairy hands their knell is rung,

By

forms unseen their dirge is sung;

There

Honor comes, a pilgrim grey,

To

bless the turf that wraps their clay;

And

Freedom shall awhile repair

To

dwell a weeping hermit there!

Farewell, gallant spirit! While thy death in trumpet tones tells us “God only is great,” may it increase our devotion for the Omnipotent Almighty, who out of the dust could create such a being as thou wast. May it increase our gratitude that our lot is cast under a government, for whose preservation you poured out the best blood in your veins. Though the sad heart-moving words, “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” have been pronounced over thy earthly remains, yet in your own burning words— and what more appropriate ornament for the bier of him who earned the title of the “Gray Eagle of Republicanism,” than a plume from his own wing, a “feather that adorned the royal bird and supported his flight?”—

Your thoughts will remain. They will go forward and

conquer. They are gathering now into a stream. They are spreading into a

rushing, boiling and bounding river. They are controlling men’s minds. They are

maturing lives. They are kindling men’s words. They are freeing men’s souls.

And as surely as the great procession of Heaven’s host above us moves each in

its appointed place and orbit, so surely shall the proud principles of human

right and freedom prevail.

And hereafter, when the “banner of Freedom streams proudly to the wind in honor of victory— when peace o’er the world extends her olive wand”— when the great and good are remembered, you will not be forgotten. We will remember the man “of foreign birth who laid down his life for the land of his adoption.” When the roll is called of Freedom’s great martyrs, your sacrifices, your fidelity to liberty, will be remembered, and ten thousand times ten thousand patriot tongues shall say of you, as it was said of another soldier in another struggle, “Fallen upon the field of honor.”

“But the last word must be spoken, and the imperious mandate of death must be fulfilled. Patriot-warrior, farewell! Thus, oh brave heart! we leave thee to the equal grave. As in life, no other voice among us so rung its trumpet tones upon the ear of freemen, so in death its echoes will reverberate amid our mountains and our valleys, until the truth and valor cease to appeal to the human heart.”

Address of Rev. Thos. Starr King.

DELIVERED AT THE GRAVE IN LONE MOUNTAIN CEMETERY, SAN

FRANCISCO, PREVIOUS TO THE INTERMENT OF COL. BAKER’S BODY.

The story of our great friend’s life had been eloquently told. We have borne him now to the home of the dead, to the Cemetery which, after fit services of prayer, he devoted in a tender and thrilling speech, to its hallowed purpose. In that address, he said: “Within these grounds public reverence and gratitude shall build the tombs of warriors and statesmen *** who have given all their lives and their best thoughts to their country.” Could he forecast, seven years ago, any such fulfillment of those words as this hour reveals? He confessed the conviction before he went into the battle which bereaved us, that his last hour was near. Could any slight shadow of his destiny have been thrown across his path, as he stood here when these grounds were dedicated, and looked over slopes unfurrowed then by the plowshare of death?

His words were prophetic. Yes, warrior and statesman, wise in council, graceful and electric as few have been in speech, ardent and vigorous in debate, but nobler than for all these qualities by the devotion which prompted thee to give more than they wisdom, more than thy eagle eye in the great assemblies of the people— even the blood of thy indomitable heart— when thy country called with a cry of peril,— we receive thee with tears and pride. We find thee dearer then when thou camest to speak to us in the full tide of life and vigor. Thy wounds through which thy life was poured are not “dumb mouths,” but eloquent with the intense and perpetual appeal of thy soul. We receive thee to “reverance and gratitude,” as we lay thee gently to thy sleep; and we pledge to thee, not only a monument that shall hold thy name, but a memorial in the hearts of a grateful people, so long as the Pacific moans near thy resting-place, and a fame eminent among the heroes of the Republic so long as the mountains shall feed the Oregon! The poet tells us, in pathetic cadence, that the paths of glory lead but to the grave. But this is true only in the superficial sense. It is true that the famous and the obscure, the devoted and the ignoble, “alike await the inevitable hour.” But the path of true glory does not end in the grave. It passes through it to larger opportunities of service. Do not believe or feel that we are burying Edward Baker. A great nature is a seed. “It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body.” It germinates thus in this world as well as in the other. Was Warren buried when he fell on the field of a defeat, pierced through the brain, at the commencement of the Revolution, by a bullet that put the land in mourning? No; the monument that has been raised where his blood reddened the sod, granite though it be in a hundred course, is a feeble witness of the permanence and influence of his spirit among the American people. He mounted into literature from the moment that he fell; he began to move the soul of a great community; and part of the principal and enthusiasm of Massachusetts to-day is due to his sacrifice, to the presence of his spirit as a power in the life of the State.

Did Montgomery lose his influence as a force in the Revolution because he died without victory, on its threshold, pierced with three wounds, before Quebec? Philadelphia was in tears for him, as it has been for our hero; his eulogies were uttered by the most eloquent tongues of America and Britain, and a thrill of his power beats in the volumes of our history, and runs yet through the onset of every Irish brigade beneath the American banner, which he planted on Montreal.

Did Lawrence die when his breath expired in the defeat on the sea, after his exclamation, “Don’t give up the ship!” What victorious captain in that naval war shed forth such power? His spirit soared and touched every flag on every frigate, to make its red more commanding and its stars flame brighter; it went abroad in songs, and every sailor felt him and feels him now as an inspiration.

God is giving us new heroes to be enthroned with those of the earlier struggles. Before our guests victories come, He gives us, as in former years, names to rally for, and examples to inflame us with the old and the unconquerable fire. Ellsworth, Lyon, Winthrop, Baker, our patriots who have fallen in ill-success, will hallow our new contest, and exert wider influences as spirit-heroes than over their regiments and battalions, while they shall ascend to a more tender honor in the nation’s memory and gratitude.

And other avenues of service than those of the earth are opened for such as he whom we are waiting to lay in the tomb. “It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory,” saith the Sacred Word. God has higher uses for such spirits. In the Father’s house are many mansions; and Christ hath prepared the place for all ranks of mortals for whom he died. The mysteries of the other world are not revealed. The principles of judgment, the tests of acceptance and of the Supreme eminence are unfolded. Intellect, genius, knowledge, faith, shall be as nothing before humility, sacrifice, charity. But in the uses of charity the fiery tongue, the furnished mind, the unquailing heart, shall have ample opportunities, and ampler then here. Paul goes to an immense service still as an Apostle; Newton to reflect from grander heavens a vaster light. As we shut the door of the tomb of genius, let it be with gratitude to God for its splendor here, and with a hope for its future that swells our bosom, though its outline be dim.

And let us not be tempted, in view of the sudden close of our gifted friend’s career, in any sad and skeptical spirit, to say, “What shadows we are, and what shadows we pursue!” The soul is not a shadow. The body is. Genius is not a shadow. It is a substance. Patriotism is not a shadow. It is light. Great purposes, and the spirit that counts death nothing in contrast with honor and the welfare of our country,— these are the witnesses that man is not a passing vapor, but an immortal spirit.

Husband and father, brother and friend, Senator and soldier, genius and hero, we give thee, not to the grave and gloom— we give thee to God, to thy place in the country’s heart, and to the great services that may await thee in the world of dawn beyond the sunset, with tears, with affection, with gratitude, and with prayer.

Transcribed by: Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

Source: Shuck, Oscar T., “Representative & Leading Men of the

Pacific”, Bacon & Co., Printers & Publishers, San Francisco, 1870. Pages 63-83.

© 2008 Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

GOLDEN NUGGET'S SAN

FRANCISCO BIOGRAPIES