REPRESENTATIVE

AND LEADING

MEN OF THE PACIFIC

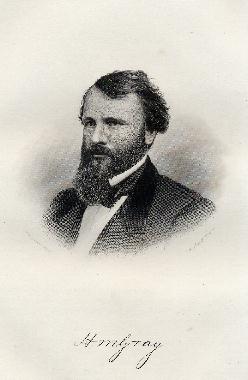

HENRY M.

GRAY

By WILLIAM V. WELLS.

The name of Dr. Gray, surrounded by endearing recollections, has for twenty years been cherished as a household word in San Francisco, where, in the relationship of friend and benefactor, his good deeds are enshrined in unnumbered hearts. He was born in New York, in 1821. His father, the Rev. William Gray, a Scotch Presbyterian clergyman, removed to Seneca Falls, N. Y., soon after the birth of his son, who passed his boyhood there. He was graduated in 1842 at Geneva Medical College, having previously studied at Almyra with Dr. Boynton, his private preceptor. He went thence to New York, commenced the practice of his profession, and was soon known for the brightness and thoroughness of his intellectual acquirements, rendered the more effective by a pleasing frankness of manner which drew about him the best influences. As Visiting Physician at the New York Dispensary, in Centre Street, he gave a certain number of hours daily to gratuitous practice among the poor, and by some of them his assiduous attentions are still gratefully acknowledged.

With an assured and enviable social position, and the certainty of speedy eminence as a physician, his love of adventure could not resist the excitement of the California gold discovery; and closing his office in New York, he organized a party of ten congenial spirits—college mates, friends and associates—who purchased the bark Hope, and sailed in July, 1849, for California, he acting as surgeon of the expedition. Touching at Rio de Janiero they reached their destination in the following December. Some of the party, including Dr. Gray, visited the mining regions, but returned to San Francisco after a few months, where he immediately commenced the practice of medicine, to which he thenceforth devoted himself.

Almost as soon as political organization began to assume shape on the Pacific coast, Dr. Gray identified himself with the Whig party in San Francisco, but never to an extent that could interfere with his professional pursuits. He had brought with him from his native State the traditions associated with the great names of the Whig party, and to that faith he adhered as long as the party maintained an existence. He was a member of the Whig State Central, and of the Whig General Committee, having been Secretary of the former and Chairman of the latter. His popularity bringing him prominently before the Nominating Committee as a candidate for Mayor in 1852, he lacked four votes of the nomination, which was awarded to Mr. Brenham, who, in the ensuing campaign was elected over his Democratic competitor. About the same time, Dr. Gray was chosen to deliver the oration at the American theatre, before the assembled Masonic lodges of San Francisco, on the occasion of the centennial of Washington’s initiation into the Order. Of this no other record remains than a few meagre paragraphs in the newspapers, by which it appears that the address was a shining testimonial of the eloquence and culture of the orator, who, with that disregard for the applause of the public, which, unfortunately, too often distinguishes genius, modesty withheld the manuscript from publication. It impressed itself upon the audience by its accomplished scholarship and the unstudied gracefulness of the delivery. His addresses before the Grand and other Masonic Lodges were of the same finished type, but were not regarded by their author as of sufficient merit to deserve perpetuation in print. On the anniversary of St. John the Baptist, June 25th, 1860, he delivered the oration at the laying of the corner-stone of the Masonic Temple in San Francisco. His notes he was induced to write out for publication only at the earnest request of his brother Masons, who claimed the production as the property of the Order. This is the sole address by Dr. Gray that has been preserved, and is hereto appended as a fair specimen of his polished and fervid eloquence.

His practice, which at first had been limited, grew to be the most considerable of any in San Francisco, and so lucrative that in a few years he had made a large fortune despite his proverbial remissness in making collections, his own expensive habits, and his liberal contributions to the many charities that appealed to him for aid. Wherever the voice of pain and anguish was heard, there the good Doctor was foremost with his cheerful presence, tender sympathies, and kindly ministrations. As in earlier days in New York he had ever been ready to assuage the sufferings of the poor and wretched, so in the home of his adoption he distinguished himself by the extent of his gratuitous practice. With him it was no theoretical abstraction, but he daily carried into practical illustration the Scriptural and Masonic teachings which raise charity to the first of the cardinal virtues. Until his last day he was a Surgeon of the Fire Department, and at any time some if its members were to be seen in his ante-room awaiting attendance, for which he desired no other reward than the consciousness of doing good to his fellow man. He was long a member of the “San Francisco Association for Medical Enquiry”—a body of physicians, who, in a quiet way, did more to alleviate distress in California than can ever be acknowledged or known beyond their own beneficent circle. Hundreds of poor creatures of either sex who came to him for treatment, he prescribed for without fee or reward, but sending them away with the means of buying not only the necessaries, but the luxuries so grateful to the sick, and beyond the reach of many a longing patient. In kind offices he was omnipresent. On board ocean steamships he found his way into the crowded steerage to attend the helpless and afflicted, and on his visit to the Yosemite, in 1861, he went far out of his route to prescribe for a wounded hunter lying in his cabin among the lonely fastnesses of the Sierras. Carrying his good deeds beyond the term of his existence, shortly before his death, he charged a professional friend with the care of the health of poor and worthy persons who had long received gratuitous practice at his hands. He made a point of inquiring into the circumstances of needy-looking people—especially women and children—seeking medical advice; and how many have gone down the familiar wooden steps at the corner of Dupont and Clay streets, leading from his office, with blessings on their lips for the cheery words and more substantial tokens of his kindness, no tongue can ever tell, nor pen record.

He entertained at one time a worthy ambition for political preferment. These aspirations originated not in a sordid craving for the emoluments of office, nor the dazzling allurements of popularity; but in the consciousness of fitness for position—an innate sense of intellectual power such as could draw towards it the best elements for efficient government. In the fall of 1853, he was nominated for Mayor by the Whigs, and shared in the final defeat sustained by that party throughout California, from candidate for Governor, down. It was the last Whig campaign. From that time he renounced politics except during the civil war, when he was a pronounced Unionist, aiding the cause by speech, money and example, and holding an official position on the staff of General Allen until the close of his life. Failing in the election for Mayor, he thereafter gave all his energies to science; and however much the city may have lost in him as a ruler, it is beyond question that the community was largely the gainer in the exclusive possession of his great professional usefulness. His father, who was still officiating as a clergyman in New York, visited him in San Francisco in 1856, and died there in October the same year, at the age of seventy.

Dr. Gray never left California except for a brief visit to New York late in 1859, where, during the ensuing winter, he suffered intensely from pneumonia, and by the advice of his medical friends, returned speedily as a means of preserving his life. His recovery was regarded as extremely doubtful—and sharing in these doubts himself, he characteristically ordered his coffin, which was lined with lead, and had preparations made for embalming in case his decease should occur before reaching California; such was his repugnance to the idea of being buried at sea. His health was improved, however, by the voyage. He was President of the Society of California Pioneers in 1861-2, before whom, in 1856, he had delivered the annual address. This alone, among numerous similar orations by others, has not been preserved, neither in pamphlet form nor in the columns of the press. He spoke for upwards of an hour from a few notes which he had arranged only the night before, and which, with his usual carelessness where his own fame was concerned, he failed to prepare for publication. It is remembered as a deeply interesting discourse, rich in historical allusions, clothed in the most captivating forms of eloquence, and picturing the past and future of California with a wealth of classical imagery and glowing beauty of diction.

It was in the theory and practice of his profession that his mind and heart were especially engaged. He was indefatigable in studies rendered necessary by the advancement of the medical and its associate sciences. Endowed with peculiar graces of mind and person, his manner in the sick room showed consciousness of his own, ability, and at the bed-side his presence inspired a confidence almost marvelous. Not seldom has his genial manner and kindness of voice arrested the course of disease by a magnetic power eminently his own. Master of his own feelings and mighty in his sympathies, how often has he bouyed up the sinking heart of agonized parent, child, and sorrowing friend. In times of danger he showed a courage and fearless use of means sometimes called heroic in practice. Nature seemed to have designed him for the work of a physician. He investigated disease almost intuitively, arriving very quickly at conclusions; though where there was the least doubt in his mind, or obscurity in the symptoms, he was careful, patient and untiring, seldom giving an opinion that was not verified by the progress of the case. After recognizing disease he was never at a loss for remedies, and had a happy faculty of making combinations to suit each individual case, never combining without being able to give a most satisfactory reason therefor. His health was such as to forbid constant application to professional duties for a year previous to his death. He was industrious however, and applied himself assiduously until October, 1862, when he found it necessary to resign the more arduous portion of his practice. Thenceforward until his death he alternately worked and rested, frequently going into the country for a brief relaxation, and returning, recommenced work with a determination far beyond his powers, until again forced to retreat. He visited San Luis Obispo and San Rafael during 1863, always working hard while at home, despite the remonstrances of his numerous friends. It seemed impossible for him to remain in the city without being engaged in active practice. His devotion to his friends was, if possible, more than reciprocated; which a single instance will illustrate, though only an example of very many similar attachments between his patients and himself. He returned, broken in health, to attend an invalid lady in a case of emergency, whom he had watched from childhood through severe illness and much suffering. Although worn down and enduring great pain himself, he was with her almost constantly for a week, when death terminated her sufferings. He was overwhelmed with grief, and never afterwards recovered himself, following his patient in about a fortnight. Three days before the death he had attended a number of patients, and was out in the street thirty-six hours prior to his decease. He died on the morning of September 24th, 1863. For eight hours previous to dissolution he was speechless, but conscious of all that was passing around him. He had often expressed a desire to die holding a Mason by the hand. In his last moments he grasped the hand of a friend present, motioning him to a seat, when he seemed content, and so breathed his last.

The announcement that Dr. Gray was dead, though it did not take his friends by surprise, fell like a pall upon many a sorrowing household. Every one who had known him seemed to take the event especially to heart, as at the loss of a near and intimate friend. Associations and public bodies met and passed appropriate resolutions. The wealthy and the poor alike were mourners—those for the genial companion, these for the generous benefactor—all for the skillful, sympathizing physician, who had carried hope, life, courage and healing into despairing hearts and homes. He died a bachelor, and upon the Society of California Pioneers devolved the sad duty of receiving the body at their hall, where it lay in state the night preceding the funeral. Quiet footsteps came continually through the watches of that night—rustling silks and the coarse habiliments of poverty mingling, as one after another lingered a moment and passed on—the suppressed emotions of the refined and self-possessed not less eloquent than more audible and uncontrolled grief. The casket, piled high with ever-increasing floral offerings, could at last hold no more, and the floor around was strewn with them. The services at the funeral, in which Civic orders and societies and Military organizations vied with each other to do honor to the occasion, were memorable and deeply impressive. The remains, with those of his father, were sent to New York, where they rest in Greenwood Cemetery, side by side.

We have endeavored thus briefly to depict Dr. Gray as the scientist, the physician, and the member of society. In conversation as in oratory he was singularly felicitous. His voice possessed that modulated musical quality rarely found except in superior organizations, and which with him, whether in every-day intercourse among his friends, in an after-dinner speech, or in the more formal parlance of an organized assemblage, had the same fascinating influence, enhanced by the charm of an unaffected courtliness of manner that made his presence eagerly sought in reunions of cultivated men and women. His personal appearance was as strikingly handsome as his manners were distinguished. He was a connoisseur in music, books, and works of art, which he was always selecting as gifts for his patients. He had a genuine appreciation of the grandeur and beauty of nature, and the correctness of an anatomist in the choice of fine horses, of which he was particularly fond. His tastes combining the attributes of manliness and intellectual culture, were those of the highly educated gentleman. His nearest associates recall him as one of the finest types of man, in his physical as well as mental qualifications. To have enjoyed his intimacy may be regarded as one of those legacies to which the mind, perhaps wearied with the world’s selfishness, instinctively turns when glancing back into the near past for bright examples and pleasant memories.

Masonic Oration

Pages

| 486 | | 487 | | 488 | | 489 | | 490 | | 491 | | 492 | | 493 |

Transcribed by: Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

Source: Shuck, Oscar T., “Representative & Leading Men of the

Pacific”, Bacon & Co., Printers & Publishers, San Francisco, 1870. Pages 479-486.

© 2008 Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

GOLDEN NUGGET'S SAN FRANCISCO BIOGRAPIES