REPRESENTATIVE

AND LEADING

MEN OF THE PACIFIC

HENRY WAGER

HALLECK

By JUDGE T. W. FREELON.

MAJOR GENERAL HENRY WAGER HALLECK, U. S. Army, was born on the banks of the Mohawk River, at Westville, Oneida County, State of New York, in 1815. He is a lineal descendant from Peter Halleck, one of the Pilgrim Fathers, who landed at Halleck’s Neck, Southold, in 1640, and settled within the limits of Aquebogue, near Mattituck.

The family name in England is Holly Oak, and Fitz Greene Halleck, the poet, traced back the lineage to the Percy family. The General’s grandfather, Deacon Gabez, changed the spelling of the family name from Hallock to Halleck—the orthography adopted also by that branch of the family from which Fitz Greene Halleck descended. The subject of this biographical notice does not, however, claim any interest in the Mount Halak territory annexed by Joshua, and which the poet used to claim as the original homestead of his Puritan ancestors.

General Halleck’s father, Joseph, was a Lieutenant in the war of 1812, and a civil magistrate in his country for some thirty years. His mother was the daughter of Henry Wager, of Oneida County, New York. He was a man of strong sense, and filled many legislative and political positions with credit. His father came from Baden Baden and settled on the Hudson River. The old mansion, with its gable end towards the street, built of bricks imported from Holland, is still standing in Columbia County. The name originally spelled, as it still is, in Germany, Waghner.

The subject of this sketch, after a preliminary academical education, and a brief residence at Union College, New York, entered the Military Academy in 1835, nominated by the late Judge Beardsley, then Member of Congress, and was graduated and promoted as Second Lieutenant of Engineers in 1839—ranking third in a class of thirty-one cadets. During his furlough, he returned to, and completed his studies at, Union College. From his graduation till 1844 he was on duty as Assistant Professor of Engineering, at the Academy, and employed on the fortifications in New York harbor. In 1845 he made an extended tour in Europe, examining into the various military establishments of the principal States. After his return, he delivered a series of lectures before the Lowell Institute, of Boston, on Military Art and Science.

In the summer of 1846 he was sent, via Cape Horn, to the Pacific Coast, and was actively employed both in civil and military capacities during the Mexican war. For gallant conduct in the affairs of Palos, Prietos and Urias, Mexico, November 19th and 20th, 1847, he was breveted a Captain. He was subsequently distinguished in the affairs of San Antonio and Todos Santos, Lower California, March 16th and 30th, 1848. At the former place, with a small detachment of mounted volunteers with whom he had made a forced march from La Paz, he surprised and defeated a Mexican garrison of several hundred men, capturing two officers and other prisoners, the colors and official records; destroying arms and ammunition, and returning to his post within thirty hours, during which he had accomplished these results and a march of one hundred and twenty miles. At Todos Santos he led the attack with two companies of the New York Volunteers, and “for his assistance as Chief of Staff,” and “for the able manner in which he led on the attack,” he was specially commended in the official report of his commanding officer.

Captain Halleck also acted as Aid-de-Camp to Commodore Shubrick in the naval and military operations along the Mexican coast, and in that capacity participated in the capture of Mazatlan, of which place he was made Lieutenant Governor. He is closely identified with the early history of California, acting as Secretary of State under the military governments of Generals Mason and Riley, and during the same period as Auditor of the Revenues. He was a prominent member of the Convention assembled in 1849 to form a State Constitution; and as an active member of the drafting committee, had an important part in the preparing of that instrument; being distinguished also for his able and determined opposition against all attempts to engraft African slavery upon this State. Between the years 1850 and 1854, he was on duty as Judge Advocate and Inspector and Engineer of Lighthouses on this coast. Having attained the rank of Captain of Engineers, he resigned from the army. In 1854 he entered into the practice of law in San Francisco, and was for many years the senior partner of one of the largest law-firms in California. He was Director General of the New Almaden Quicksilver Mine, 1850-61; President of the Pacific and Atlantic Railroad from San Francisco to San Jose, 1855, and Major General of Militia, 1860-61.

Soon after the breaking out of civil war he returned into the army, being appointed on the recommendation of Lieut. Gen. Scott, a Major General, August 17th, 1861. From November of same year till March, 1862, he was in command of the Department of the Missouri, holding also a commission as Major General of Missouri Militia. During this period he was actively engaged in reconstructing a chaotic department in which material was wanting and the personnel was demoralized, and in directing offensive operations against the enemy. He had the principal directions of the military movements resulting in the successful campaigns of the West, commencing in February, 1862.

In March, 1862, General Halleck assumed command of the Department of the Mississippi, and in the following month took immediate command of the army before Corinth. The investment of this place was, under his personal direction, conducted to a successful issue, notwithstanding obstacles almost insurmountable. Deficient in the means of transportation, he advanced over and in roads nearly impassable, and through forests that might have been deemed impenetrable by any other troops than those under his command.

After the unfortunate termination of General McClellan’s campaign, resulting in the withdrawal of an heroic army from the front of Richmond to the banks of the James, the President decided to call a soldier to Washington, to assume, under his direction, a general control over all the armies of the United States. General Halleck was selected by the administration for this purpose, and was at once summoned to Washington. But, being fully aware that the position would involve great responsibilities—without corresponding powers to direct —and that therein he would find the duties extremely arduous, harassing, and utterly thankless, he asked that he might be allowed to remain with his own troops. The President’s order, however, succeeded the invitation, and the General cheerfully entered upon the duties of his new position, assuming command of the army in July, 1862. He thus sacrificed the opportunity for reaping personally the results which followed the operations initiated and, to a great extent, conceived by him, and which were so gloriously executed by our Western armies. He was in command of the army till March, 1864, when he was relieved at his own request, and in view of General Grant’s promotion to the grade of Lieutenant General. He then, at the urgent request of the President and at the desire of General Grant and the Secretary of War, remained at Washington and acted as Chief of Staff of the Army till cessation of hostilities. The duties of this position, anomalous in our service, were, inasmuch, as the General-in-Chief was permitted to take the field, essentially the same as those that he had been permitted to exercise as commanding general. The embarrassments were somewhat increased, while the power of individual action was even more restrained. In view of his own experience at Army Headquarters he advised General Grant to remain away from the stronghold of the politicians, and to seek safety from their mines under the fire of Lee’s Army. In this advice he was most cordially sustained by the brilliant Sherman.

Upon General Grant’s return to Washington, after receiving General Lee’s surrender, General Halleck was sent to Richmond in command of the Military Division of the James, and was specially charged with the reëstablishment, so far as practicable of loyal civil government in Virginia. In July, 1865, he was assigned to command of the Military Division of the Pacific, and returned to his home and assumed that command in August of same year.

The General is the author of a work on “Bitumen: its varieties, properties, and uses,” 1841: of “Elements of Military Art and Science,” 1846—and a second edition, “with critical notes on the Mexican and Crimean Wars,” 1858; of “A Collection of Mining Laws of Spain and Mexico,” 1859; of a work on “International Law, or rules regulating the intercourse of State in Peace and War,” 1861, and of “A Treatise on International Law and the Laws of War, prepared for the use of Schools and Colleges,” 1866. Translator and Editor of “De Fooz on the Law of Mines, with introductory remarks,” 1860; and of “General Jomini’s Life of Napoleon,” with notes, 1864.

The Degree of A. M. was conferred upon him by Union College in 1843, and that of LL. D. in 1862. His published works alone are enough to make a reputation for any reasonable man, and will always remain a monument of his learning and industry. They are constantly quoted as authority in the Courts. We have heard one Judge of the Supreme Court of the United States say that upon the “rules of war” the Supreme Court considered General Halleck as “the best authority.” But his double life of civilian and soldier has been so full, so crowded, we may say, that his authorship seems almost a secondary thing in his history.

In September, 1848, he was appointed Professor of Engineering in “Lawrence’s Scientific School” of Harvard University, Massachusetts, which appointment he declined.

General Halleck has been one of the best abused men in the country. As General-in-Chief he was forced to occupy a position misunderstood, even in the army. It was one of responsibility without power. He had no authority to act otherwise than was approved by the President and the Secretary of War. He could simply advise them, and then act as they saw best; the nation holding him responsible for the simple execution, in good faith, of orders that were oftentimes in direct conflict with his own judgment. When General Grant succeeded him the people had become heartily tired of the mixed Directory, and Congress conferred upon the General powers that had never been granted to his predecessors.

General Halleck exhibited a commendable spirit of self-sacrifice in remaining in Washington as Grant’s chief-of-staff, after his own experience of the annoyances surrounding an army Headquarters so inconveniently near the seat of Government.

The General has certainly betrayed none of the professional jealousy supposed to be characteristic of military men, and which has impaired the usefulness of some of our most prominent soldiers. It was he that first discovered and nourished the war-like qualities of Sheridan. It was he that recommended, first, Buell and Grant, and then C. F. Smith for promotion as Major Generals of Volunteers—Badeau being mistaken in asserting that Smith was recommended before Grant. He was also an earnest advocate of the claims of Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Meade, and McPherson, for promotion in the regular army. During the war he was in most cordial coöperation with these distinguished men.

It was Halleck that sustained Grant while in difficulties, both after Fort Donelson and after Pittsburg Landing. On the latter occasion the steady support of his commanding General was of vital importance to the present Chief Magistrate. The pressure brought upon General Halleck by the President, Secretary of War, and several of the Western Governors, for the removal of Grant from all command, was almost irresistible. To save him from being absolutely shelved, General Halleck placed him second in command to himself, it being impossible to continue him at that time of popular prejudice in command of one of the armies. These circumstances have been gravely misrepresented by Badeau in his life of Grant. It is not true that Halleck ever issued orders for Banks to supersede Grant at Vicksburg. Such action was undoubtedly discussed by his superiors, but General Halleck had no desire to see Grant superseded.

Again, just before the battle of Nashville, General Grant becoming impatient at the apparent slowness of Thomas’ movements, directed that he should be relieved; but Halleck’s faith in Thomas was so strong that, although entirely unsupported by the Administration in such action, he assumed the responsibility of withholding the order. A glorious victory was the result of the opportunity thus preserved to General Thomas.

The friends of McClellan charged his removal from command to Halleck’s influence; but although urged by the Secretary of War, and nearly the entire Cabinet, to join with them in recommending that change, he refused to comply.

Neither was General Halleck responsible for the appointment to or removal from command of Burnside or Hooker. When it was determined, however, to relieve the latter, the General recommended Meade as his successor.

General Halleck married, in 1855, a granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton, and daughter of John C. Hamilton, Author of “History of the Republic of the United States,” “Life of Hamilton,” “Works of Hamilton,” etc. He has only one child, a son, now thirteen years old. The General is a very wealthy man, having made his fortune out of the professional emoluments of his practice of law in California. His firm, owing in a great degree, to the knowledge of the Mexican language, and titles, and customs acquired during his early residence on the Pacific by the General, did probably the largest and most profitable land business in procuring the confirmation of Spanish grants, ever done in the United States by one law firm.

In June, 1869, under orders from headquarters at Washington, General Halleck relinquished to General Thomas the command of the Department of the Pacific, and assumed that of the Department of the South, with headquarters at Louisville, Kentucky, where he is now stationed. He lives in a style becoming his position and means, but entirely without ostentation—cautious, wise, of untiring industry, of great research—having at command vast stores of patiently-acquired information upon almost all subjects. Conservative and just by nature, he is calculated to be a safe adviser, and we trust and believe that his days of useful service are only commenced. He showed, when a young man, in the actions with the enemy in Lower California and Mexico, that impetuous personal bravery so befitting the young soldier, and indeed so necessary to make up the perfect commander. At West Point, in matters of discipline especially, he was always looked upon, even when a boy, as an authority, and his boyish decisions are even yet quoted at the “Point.”

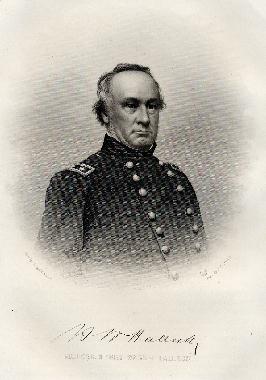

The portrait accompanying this sketch gives a fair idea of his personal appearance, and justifies the sobriquet given him by his soldiers of “Old Brains.” He is about 5 feet 11 inches in height, and weighs about 190 pounds. His smile is very genial, and his whole bearing is courteous and dignified.

General Halleck belongs peculiarly to California, and is identified with its history; he owes it almost all, and it owes him much. Until the breaking out of the civil war, he always voted with the Democratic party, and his sympathies are with that party, except inasmuch as they have been changed by the events of the war. When peace was declared between the United States and Mexico, General Halleck was perhaps the most influential and best known man in California; but he is not fitted for the arts of successful politician, otherwise he would undoubtedly have been sent as one of our first Senators to the National Capital. As it was he received 18 votes for U. S. Senator, which were almost enough to elect. He is a member of the Society of Veterans of the Mexican War, an organization in which he seems to take much interest. His home is in California, and we may well be glad that we have so sagacious and so able a man ready in war or in peace to aid and to guide us. This is not the time to discuss his qualities as the great general, nor are we qualified for the task; but we may be permitted to say that it is by no means proven, that under the same circumstances he would not have been the equal of the best soldiers the war has produced.

One Napoleonic quality, we certainly know he possessed in a high degree—the power of judging and choosing men. Always, from the first, he recognized the lofty military merit of such men as McClellan, Sherman, Lee, Thomas, and others, and the qualities of that most successful of all of them—our present President.

History will do justice to the great

services he rendered his country, while performing his arduous and delicate

duties at Washington during the war. His negative services were, perhaps, even

more valuable than his positive. Officially associated with civilians claiming

to understand the whole art of war, whose policies and plans were constantly

changing, a “break and a balance-wheel were both absolutely needed. We believe

that General Halleck was the right man in the right

place at the right time, and did as much as any human being could do

under those anomalous and fearful circumstances; and posterity, when all is

known, will honor him for what he prevented as well as for what he accomplished.

Transcribed by: Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

Source: Shuck, Oscar T., “Representative & Leading Men of the

Pacific”, Bacon & Co., Printers & Publishers, San Francisco, 1870. Pages 375-383.

© 2008 Jeanne Sturgis Taylor.

GOLDEN NUGGET'S SAN

FRANCISCO BIOGRAPIES