REPRESENTATIVE

AND LEADING

MEN OF THE PACIFIC

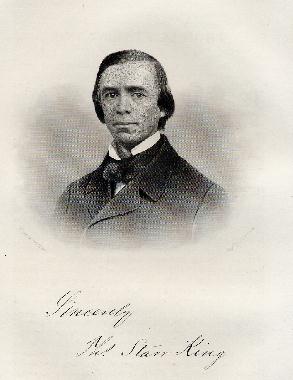

THOMAS STARR KING

The Editor desires to assure the public that he has left no stone unturned in the effort to obtain an original sketch of REV. THOMAS STARR KING. The career of this man was so brilliant and eventful—in the brief compass of forty years, he accomplished such mighty purposes—that his life and deeds deserve to be chronicled by a gifted and practiced pen, entirely familiar and in harmony with the theme.

For the purpose of securing such a sketch,

the Editor approached or communicated with many of the most polished and

effective writers of the Pacific—and

also of the Atlantic States—and

in so doing, exhausted the list of those whom he knew to be intimate friends

and admirers of Mr. King, when living, and whom he considered competent to the

task.

All,

for various reasons, declined to furnish the desired sketch. Having had only a

casual introduction of Mr. King a few years before his death, and not having

enjoyed any intimacy with him; and moreover, knowing nothing of his career

prior to his arrival in California the Editor felt his incapacity to treat the

subject properly, and had nearly concluded that his work would have to be given

to the public in an incompetent state, owing to the omission of a biographical

notice of this truly representative man. But a short time before the manuscript

was placed in the hands of the printer, he was presented with an address read a

few days after the decease of Mr. King before the Unitarian Society, of which

he was Pastor, by a prominent citizen of San Francisco, who had for several

years been a warm personal friend of Mr. King, and who had received from his

dying lips the injunction: “Keep my memory green.” This gentleman was then, as

he had for some years previously been, a well known merchant, and also

Superintendent of the United States Branch Mint of San Francisco. The

description of the death scene of Mr. King, of which the author was an unhappy

witness, is fraught with absorbing and melancholy interest.

This address, however, discloses no information concerning Mr. King’s ancestry, birth, boyhood, or any portion of his career passed to prior to his arrival in California, but the San Francisco Bulletin, on the day of Mr. King’s death, contained an ably-written editorial, eulogistic of his splendid talents and his great services to the State. And the local columns of that journal gave a brief notice of his life, on the same day, and, a few days later, contained a full account of the solemn ceremonies and impressive scenes attending his burial.

These articles in the Bulletin newspaper, and the address alluded to, together make up a faithful and interesting history of Mr. King; and the Editor gives place to them here, in lieu of an original sketch, confident that they will be accepted by an appreciative public as a worthy memorial of his life and services.

From the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, March 4th, 1864.

THE ANNOUNCEMENT of the death of the REV. THOMAS STARR KING startles the community, and shocks it like the loss of a great battle or tidings of a sudden and undreamed-of public calamity. Certainly no other man on the Pacific Coast would be missed so much. San Francisco has lost one of her chief attractions; the State, its noblest orator; the country, one of her ablest defenders. Mr. King had been less than four years in California, yet in that short time he had done so much and so identified himself with its best interests, that scarcely one public institution or enterprise of philanthropy exists here which will not feel that it has lost a champion. He was a vast power which any struggling good work could command. The most erudite and the least cultivated were alike charmed by the eloquence of his popular addresses.

He warmed the coldest audience into enthusiasm. Some said it was his musical voice; some that it was his genial manner; some that it was his tact in feeling his audience and humoring it until every fraction of it was “in sympathy” with him, when he boldly led off to the point he had in view; some, in more general terms, that it was his commanding genius; some that, it was the merits of his cause, which it was his gift to lift up and present in its best light, that accounted for his sway over the multitude; but on this all agree, friends and opponents, that while the matter was in his hands there was no gainsaying him. Few public speakers were bold enough of choice to follow with a speech after he had spoken; and if he were announced, the audience was never satisfied till his turn came.

Mr. King had grown immensely as a public speaker since he left the East. He brought with him a most enviable reputation as a literary lecturer, a polished, brilliant writer and preacher. Those who knew him congratulated California on his coming; they said he would do for our landscape and our land what he had done for New Hampshire; for his White Hills, their Legends, Landscapes and Poetry, had made the White Mountains classical, and brought them within the circle of all Eastern summer tourists. The most sanguine never imagined that he would become the power that he quickly proved himself at the sterner, harder duties that engage men who lay the foundations of States. He used to say, soon after he arrived here, and when he found how much greater would be his influence with this people if he could speak as well extempore as he wrote, that he would give anything if he had the ability to “think on his feet.” “Beecher has it,” said he; “his thoughts come trooping in never so swiftly, so orderly, and in such force as while on his feet with a great audience before him—every upturned face is his ally in marshaling his grand thoughts; but I can’t.” Few men at the height of their fame venture the experiment of a new style of address. He ventured, and every one who has heard his later off-hand speeches will testify how speedily he acquired the faculty which he coveted—of thinking on his feet—his best things flashing into his own mind apparently the instant that they flashed through it into his audience. Mr. King introduced himself to the San Francisco community by a course of lectures delivered one each week in the First Congregational Church, which was crowded to its utmost capacity to hear them. It is safe to say that fifteen minutes after he began the delivery of the first one, his position as an incomparable lecturer was established. That series had been delivered at the East. Each one of them was a perfect gem in its way. Not a sentence in one of them but gleamed with beauty. The rare and dainty imagination of the lecturer discovered itself in every phrase, and showed him a poet in the disguise of prose. The skeptical said it was very pretty writing certainly, but they doubted his depth. The lectures that Mr. King wrote here were of altogether a different order. He availed himself of that injunction of the rhetoricians, not to be too evenly excellent in your style. He polished his sentences less, he waited no longer on fine fancies; he argued more; he dropped down to good plain talk for minutes together in his addresses; and then, when his hearers were rested, he blazed out with passages that swept away all thoughts but of the one topic that possessed him.

THOMAS STARR KING was born in New York, December 16th, 1824. His father was a Universalist minister, settled in 1834 over a congregation in Charlestown, Mass. At the time of his father’s death, Mr. King was preparing to enter Harvard College, but this event left the family in a manner dependent upon him for support, and from the age of twelve to twenty, he was employed either as a clerk or school teacher. All this while he was an ardent student; scarcely were the regular duties of the day done, than the interregnum found him at his desk; and midnight looked in upon him deep in books, theological studies claiming his attention mainly. Following the bent of his mind, he devoted himself to the ministry, preaching his first sermon in the town of Woburn, in September, 1845. He subsequently preached at Charlestown to the congregation of which his father had charge.

In 1848, at the age of twenty-four, he was called to preside over the Hollis street Unitarian Church, in Boston. The church at this time was very much divided, so much so that it was feared that harmony could not be restored. Under the ministry of the energetic young pastor, however, peace once more came to its councils; the church grew rapidly in strength; and when Mr. King left, it enjoyed a prosperity unprecedented in its history. The same genial and sympathetic manners which won him the affections of the whole people of this city, as well as of his immediate congregation, endeared him to the congregation of which he had charge in Boston; and when he announced to the latter his intention of changing his residence and making this coast the scene of his future labors, a storm of regrets and remonstrances arose which would have made a weaker man change his purpose. He received the call from the Unitarian Society of this city early in the year of 1860, and sailed from Boston in the month of April. In a letter to his Hollis street Church, informing them of the call to San Francisco, he gave two reasons for his acceptance of it. One was his failing health, which made a change of climate necessary; the other, and the principle one, a desire to do the will of his Master.

He identified himself at once with California and its people, urging their interests on all occasions with a zeal and persistence which could not have been exceeded had he been one of the first settlers of the country. He looked beyond the pulpit, and mingled much with men—touching life at nearly all points. The agricultural and mineral resources of our State claimed a large share of his attention, and his lectures, illustrated by quaint humor as well as by deep and practical knowledge of his texts, are fresh as the sound of words spoken yesterday in the ears of our people. His was one of those lovable natures, which warm to all men, and in consequence his circle of friends was only bounded by his acquaintance—it is questionable if he ever had an enemy among all who knew him, even those who differed from him in theological views yielding to the magnetic sway of his voice and manner. He did not think that the pulpit, the prow of the world, should be shut out from pointing the way in politics when great principles are involved, and early in the war he pronounced against the rebellion and the issues upon which it was conducted. In this respect he has wielded a powerful influence, lending his aid to the preservation of harmony in a State which at the outset seemed likely to be divided, carrying the masses with him by that energy and eloquence which was given him as a birthright, and of which only the hand of Death could rob him.

Mr. King’s energy has an eminent illustration in the history of his pastoral labors. He found the Unitarian Society some $20,000 in debt, small in numbers and feeble in strength. In less than a year the whole debt was paid, and the society was in a flourishing condition; before four years had expired a new church was built for him, costing $90,000—to which he himself was the largest contributor, giving from his own pocket $7,000 to the church and in furniture. Barely had the building been completed when the pastor was taken away. This seems irreconcilable with faith, but the ways of Providence are often inscrutable. His physical health, never very robust, suffered much from his arduous labors, and particularly from the exertions which he put forth to insure the completion of this church and its freedom from debt. For two or three months before his death, it was evident that he was not so well as usual, and he had frequently spoken of the necessity of giving up all literary labor. He thought it would be impossible for him to endure another year of work, and they were already agitating the question of who should fill his pulpit while he took a year’s respite from labor in travel.

Just before his sickness he had a dream which he narrated to a friend at the time, remarking that it made more impression on him than he cared to confess. In his dream he thought he was shaving himself, and the razor, slipping, gashed his throat. Physicians who were called told him he could not live ten minutes. He argued the case with them—holding the edges of the wound together with his hand—telling them neither the windpipe nor any of the arteries were severed, and that he could recover if they would only stop the bleeding. They said it was useless, however, and that he must prepare to die. The dream was probably induced by the pain which had already begun to settle in his throat.

About two weeks before his death he first complained of not feeling well, and of some trouble with his throat. His friends urged him to be more careful, and not expose himself to the air; but he thought it was only an ordinary case of sore throat, and declined to confine himself or call in the aid of a physician until Friday, Feb. 26th. In the evening he had his regular reception, and between 10 and 11 o’clock went down to a social gathering at the church, though still suffering. On Saturday evening he had invited a number of friends to supper, but when evening came he was unable to appear at table. While supper was going on, however, a bridal-party came to be married. Mr. King had received no previous intimation of such a visit, and sent down asking to be excused, saying that he was sick and confined to his bed. The party replied that they had set their hearts on being married by Mr. King, and would come up to his bedside sooner than be defeated in their desire. With that spirit of self-sacrifice for which he was so remarkable, he then said he would get up and go down into the parlor. He did so, and went through the ceremony; but though it was performed in a very few minutes, he was so weak at its conclusion that he had to be assisted up to his room.

From the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, March 7th, 1864.

THOMAS STARR KING dead had a larger congregation than he ever had living. At 9 o’clock in the morning the doors of the church were opened, and until noontime a congregation numbered by thousands and comprised of all religious denominations, poured through the aisles, bending over the burial-case where the former pastor lay with hands crossed in dumb prayer—listening to the mute but eloquent sermon of the upturned face and lips set in eternal supplication. Loving hands had festooned the church with wreaths of Egyptian lilies— those flowers which with their single petal, waxen white, suggest the tomb, and all the sad thoughts and ceremonies that attend even the greenest grace—National banners, their bright stars clouded with crape and their crimson stripes veiled, draped the altar and threw their folds over the coffin; the mantle of patriotism which fell upon his shoulders in life, enveloping and shrouding the form within in death. The apron of the Order of which he was Grand Orator, and other signs and symbols of the Masonic craft, were there; flowers of the rarest odor shed their perfume over the body, and on the breast lay a chaplet of spring violets, placed there by the request of a lady once a resident of this city, now dwelling at the East,* who telegraphed on Saturday to one who, like her, loved the deceased: “Put violets for me our dear friend who rests.” It was a kindly thought, prompted by the graceful tenderness of a woman’s heart; the flowers will be fragrant in the grave as the memory of the deceased is in the hearts of his friends—and these are only numbered by the city’s population.

A military guard detailed for the duty was stationed in and about the church, preserving order among the dense crowd, which so early as noon-time began to throng about the doors. The butts of muskets rang on the marble floors beneath which one was to sleep who believed that Christians may wear armor when the cause is just, and prayer be helmeted and mailed, if the vindication of great human principles demands it. It is safe to say that this city for many years. The congregation first passed into the church, and found their accustomed pews; the Governor and other State and Governmental dignitaries were seated, and then the main doors were thrown open for the reception of as many others as the church could contain. Not a square inch of floor was left in body, or aisle, that was not pressed by some foot. The gallery groaned with its great human freight like a ship at sea, on whose decks a mad weight of water has leaped; and so crowded looked the faces in that great bracket of life affixed to the walls, that the effect was stereoscopic and all seemed to resolve themselves into one. So densely were the audience packed that several ladies fainted away, and even men struggled to the doors for air. But there was no exit; for lobby, vestibule, and even the street for a block or more was packed with human wedges. So thick was the crowd outside that the street was only passed with difficulty after long and tedious urging. It was like bees, swarming on the outside of a hive; while through Stockton street, north and south, a tide of people going and coming, flowed in one continuous wave.

The service began at 2 o’clock, with a voluntary on the organ, by Mr. Trenkle. A most impressive scene was afforded. The solemn notes swelled through the church in a plaintive, mournful psalm; the instrument seemed for the moment to have a human heart within its walls, wailing its grief in sounds that were like the falling of tears. In the front pews of the church sat the Masons, each wearing an acacia sprig, and the habiliments of the Order. Through the stained glass of the ceiling and the sides, and the great rose-window at the end of the church, the afternoon sun sifted its mellow rays like a benediction, crowning the coffin and altar with a glory of light and color. Minute guns from Alcatraz mingled their heavy bass with the notes of the organ—soon a nearer battery in Union Square took up the burden, and there was an anthem of cannon swelling with its grand diapason the solemnity of the services. This is said to be the first time in the history of the country that minute guns have been fired by order of the Government in honor of a civilian who never held a public position.

*Mrs. Gen. J. C. Fremont.

The 39th Psalm was chanted by the choir, and following this the Rev. Mr. Kittredge read the 23d Psalm—the one which Mr. King repeated on his death-bed. The Grand Master then commenced to read the impressive burial service of the Masonic ritual, choir and organ chanting the responses. The first prayer of the ritual was offered by Mr. Kittredge; and the remainder of the service, slightly varied in accordance with the unusual burying-place, was read by the Grand Master. At the proper interval in the service the vault beneath the altar was opened, and amid a voluntary from the organ, the coffin was lowered down to its last resting-place, the Secretary of the Lodge dropping his roll upon it, and the Grand Master his acacia branch. The last prayer of the ritual was offered by the Rev. J. D. Blain, benediction was offered by Mr. Kittredge, the Masonic Brotherhood filing past the vault flung into it the acacia sprig emblem which each wore on his breast, the ceremonies were ended, and the great crowd went out into the streets and to their homes.

Besides the anthems by the full choir, solos, “I know that my Redeemer liveth,” and “Come, ye disconsolate,” were sung, the former by Mrs. Grotjan, the latter by Mrs. Leach. All through the city, during the day, with scarcely an exception, at all the principal buildings, and also at the forts, and army headquarters, national flags were at half-mast; and colors at the residence of nearly off the foreign Consuls were similarly lowered. Most of the American shipping in harbor lowered its bunting, and the foreign shipping, almost to a vessel, followed the example, the flags of Hamburg, Columbia, Russia, France and Great Britain being among the others thus displayed. On board the only war vessel in port, the Russian steamer Bogatyre, the Russian ensign, lowered from the peak, stood at half-mast during the day. If anything can mitigate the grief of his friends for his death, some flowers of consolation may surely be plucked from the fact that he was thus universally mourned. The following telegram was received from the Rev. Dr. Bellows:

NEW YORK, MARCH 5th, 1864.

To the People of California —The sad tidings of to-day have broken our hearts. Thousands here will weep with you over his bier. You have had our brightest, our noblest, our best—and he has lived and died, in the fullness of his manhood, in your service. Who shall fill his place on the platform, in the pulpit, in the hearts of a million of friends?

His full, quick, penetrative mind, winged with fancy and with restlessness in the service of truth, liberty and righteousness—his soul glowing with natural sympathy, Christian patriotism, universal philanthropy; his every action made to utter and diffuse the noble, inspiring convictions of his pure, loving nature; his eye the window of an open, honest, fervent soul—his whole character “made up of every creature’s best;” strong and gentle, generous and prudent, aspiring and modest, controlling and deferential, “the people’s darling, yet unspoiled by praise;” knowing the world and its ways, yet clean of its stains; pious without sanctimony—what but his own living, undying confidence in the absolute goodness of God can enable us to sustain such a measureless loss? The mountains he loved and praised are henceforth his monuments and his mourners. The White Hills and the Sierra Nevada are, to-day, wrapped in his shroud. His dirge will be perpetually heard in their forests.

Farewell, genial, generous, faithful and beloved friend! Thou hast gone from those who loved thee well, to One who loves thee best. God comfort thy family, thy flock, thy broken-hearted friends on both sides of a continent.

Resolutions.

At a meeting of the congregation of the First Unitarian Society held at their church on Geary Street, on the evening of March 15th, 1864, the following resolutions were offered, viz:

It having pleased the Most High God to draw closer to His side His servant, our greatly beloved and honored pastor, THOMAS STARR KING, and inasmuch as this requisition, coming to him in the plenitude of fame, intellect, and usefulness, found him still “happy, resigned, trustful,” it becomes us as Christian brethren to restrain the natural, but selfish impulses of grief, accepting the chalice commended to our lips, and bowing humbly to the Omnipotent will. Therefore be it:

Resolved, That in the sublime spectacle of the deathbed of Thomas Starr King, we

recognize a full and triumphant vindication of his faith as a teacher and his

works as a man.

Resolved,

That though it hath seemed fit to the Almighty to remove his mortal presence

from among us, the subtle influence of his piety and genius still exists, and

continues to transfuse and possess us; and that although the pulpit of the

church he has adornedremains empty, an emanation of

his goodness still obtains in the pulpit of each man’s hear swaying and

controlling its impulses directing and guiding its promptings, and preaching

“with the tongue of men and angels.”

Resolved,

That his ministration of this Society has been vital, creative and

enduring; that it has been uniformly characterized by ceaseless toil and

unabated zeal, even to the sacrifice of health and the precipitation of death—by an eloquence earnest, truthful and

convincing—by crudition thorough, complete and

reliable—by fervor, boldness and originality that have attached the lukewarm

and indifferent—by a humanity that was broad, catholic, all-sympathizing and

tolerant—by a gentleness that was winning without being weak—by a force that

was decisive in results, though unfelt in its processes—and by those rare,

indefinable social graces and courtesies which, as they were not beneath the

Guest of the bride of Cana, are the attributes of a

Christian gentleman.

Resolved, That as citizens of this republic we deplore, with the nation, the loss of a courageous heart and brilliant intellect ever ready to battle in its defense, and that we deeply sympathize with the wounded soldiers in battle-fields and hospitals, who will miss the priceless aid of him who yearned to them out of the brimming fullness of his patriotism, charity, and love.

Resolved, That we tenderly

sympathize with the deep affliction of that family circle of which he was the

life and light—offering to the

stricken widow what consolation may be derived from the assurance, that a

community are partners in her sorrow; to his widowed mother and kindred in a

distant part of our country, the expression of our unfeigned grief, that they

are bereaved of the wise counsels and affectionate solicitude of a noble son

and brother; and to the fatherless children, the undying record of his fame as

an inheritance and example to them forever.

ADDRESS

of R. B. SWAIN, ESQ.

Previous to their passage, MR. R. B. SWAIN rose and said:

Before the resolutions are adopted, I cannot refrain from bearing my testimony to the purity of Mr. King’s life, and offering to this memory the tribute of my profound admiration of his character, his genius, and his talents. I was early brought in contact with him—first by correspondence before his arrival, and afterwards as a co-laborer, though comparatively a humble one, in the cause of the church and of liberal Christianity. Knowing him so intimately, I have taken some pains to reduce to writing the thoughts that have occurred to me in reference to his life and his early death, in order that I may present them in a regular and consecutive form. For what relates to our beloved pastor, should now be the property of the Society over which he presided, and of which he was the life and light. His sayings and doings—his acts of mercy—his goodness of heart, constantly prompting him to deeds of charity—his transcendent genius, which shone forth most brilliantly in the privacy of social and familiar relations—his innate purity of character—his own comfort to promote the comfort of others—his humility, which rendered him incapable of knowing his own goodness and greatness, and oftentimes led him to estimate too feebly his own powers—his reverence, which carried his soul above the transitory things of earth, and gave him aspirations towards Heaven and his God;—all these constitute an endowment of priceless memories bequeathed to the Society in whose service he so faithfully labored, and for which he died. In the few remarks I have to offer the resolutions, I shall confine myself chiefly to narrative; but I would not, if I could, withhold the repeated expression of my love of him as a man, a patriot, and a Christian—the most pure in his thoughts, the most unselfish in his character, with whom it has been my good fortune to be associated.

I said I first knew Mr. King through correspondence. After departure of our former pastor, Mr. Cutler, and during the temporary ministration of Mr. Buckingham, the Board of Trustees negotiated, through friends at the East, for a permanent pastor. We were slightly encouraged to believe that Mr. King, then presiding over the Hollis Street Society in Boston, might be induced to come here; and through a Committee of the Board, Mr. Brooks and Mr. Lambert, who were fortunately in Boston at that time, negotiations were opened with him upon the subject. I must confess that I had but little hope that he could be secured for this Society—for I knew how he was loved and prized by his own parishioners, for whom he had done such essential service during a period of ten years, and how his fame and reputation as a divine and lecturer were as wide as the continent itself. But we believed that he would have a great field here; and were encouraged to hope that his comparative youth, his spirit of self-sacrifice, and the necessity of seeking a new field of labor to renew his physical energies, which had been much exhausted by study and over-exertion, would tempt him to listen, at least, to our call, and perhaps to adopt for a season this vigorous and prosperous State as the field of his labors. Fortunate, indeed, was it for this Society, and fortunate for California, that he came. Without him, who can now say what would, to-day, have been our condition? Who can now say that we would not have been hurled into the vortex of secession, or that there would not have been inaugurated the scheme of a Pacific Republic, for which our delegation in Congress were maneuvering, and which would have made this happy, peaceful State, a scene of fire and blood, between the contending fury of loyalty and treason?

Mr. King’s first communication, in answer to our call, was made in the month of September, 1859, to the Committee then in Boston. It is an admirable illustration of his frankness and candor, and although a private letter, there are no good reasons why the most of it should not be read here. His peculiar sincerity and earnestness are stamped in every line. Dr. Bellows, who, I am proud to say, was my pastor for many years in New York, had been commissioned, in conjunction with the Committee, to obtain a pastor for us—but they had been enjoined to make application to no man whose fame was not already secured, and whose name was not eminent among the ministers of our faith—for it was certain that with any feebler man, our then tottering Society would become bankrupt and ruined, perhaps forever. How well the task was performed, let the present condition of our Society, and indeed, let the prosperity of our State, to-day, answer. Aided by the powerful influence of Dr. Bellows, negotiations were opened with Mr. King direct. At that time his own Society, to which he had devotedly attached himself, was claiming a continuation of his services, and a Committee from a strong Society in Cincinnati were clamoring loudly for him to remove thither, and become their pastor, offering inducements which no ordinary man—no selfish man—could have resisted. As Chairman of the Board of Trustees, the correspondence fell to me. Facts and figures as to our prospects were sent to Dr. Bellows. Nothing very flattering as to the past could be presented; but our prospects, with a strong man, were set forth in brilliant colors. It seemed quite certain that there was a large field for the growth of our faith in this State, under the leadership of such a man as Mr. King proved to be, and our claims were pushed with all possible zeal, and even with audacity.

The letter which I now propose to read to you, convinced us that Mr. King, of all men, was best adapted to our wants; and notwithstanding he was constrained to answer our call in the negative, we refused to abide by his decision. The letter is as follows:—

MY DEAR SIR: I was on the point of writing to you in Brattleboro, when your letter of this morning came.

It has been impossible for me to reply at an earlier date. I have been very busy consulting intimate friends, obtaining information, and forecasting the trouble, difficulty, and losses of uprooting myself and family here, while not a little time has been absorbed in studying my own inclinations, heart, and resources, for such duties as the post in San Francisco would demand.

The result of all my inquiries, consultations and reflections, stands thus: 1st. Very grave doubts as to the ability of the parish to pay the salary named to me. Gentlemen who know the Unitarian Society there pretty well, have assured friends of mine that the parish is not united— that there are a great many great draw-backs to the popularity of a liberal faith in the city, and that with a debt of $12,400 on which the Society pay 12 per cent. interest, and a floating debt of $1000, no man with talents less electrical than Chapin’s, Beecher’s, or Dr. Bellows’, could put the parish in a condition to pay such a salary. And I am assured that I could not live in San Francisco—being myself a very poor economist—for less than $5000, at least, with my family.

I find that I must sacrifice nearly $2000 on house and furniture and books, if I uproot here. Then there is the expense of removal with my wife and daughter; then the cost of setting up anew out there, the return expenses, and the new housekeeping costs, two or three years hence, if I come back.

The risks are great. I am a poor man; I have worked very hard for ten years, have had heavy extra expenses, which still continue, and can not afford to give up such certainties as are before me here, for the ventures of so distant a field of labor. Every year my lecture opportunities enlarge. I should abandon that field in going to San Francisco, and might not be able to reënter it so favorably.

Then beyond all this, I have misgivings as to my qualification for such work as your Society needs, to fill the Church with numbers and enthusiasm. I am not extempore enough—so I fear. You need a temperament like Dr. Bellow’s, or a stirring preacher like Chapin, to enable the parish to fulfill such promise as Mr. Swain’s not to me contained. From all that I have heard and thought, therefore, I dare not trust to my power of infusing ability enough in the parish to produce the requisite receipts. I have too much at stake.

Yet I feel very strongly the attractions of the field. If I could properly go to San Francisco on a smaller salary, I would gladly do so, and work to the best of my power for the good of your parish and our noble cause. Or if I could have gone out to California on the invitation of the Mercantile Library Association, last spring, independently of the parish, and preached in the city and surveyed the field of lecturing, I could possibly have found firm ground for an affirmative reply to your call.

But as the whole subject has shaped itself, since my inquiries and serious thought, and with the firm conviction that many of the inducements must prove illusory, nothing seems to be left to me, at present, but to decline the call. Several of my own parishioners were disposed, at first, to the movement; and would be still if they were convinced that the basis is firm. But they cannot advise me, otherwise than against it, as matters look to them now. I have told you frankly my whole mind, and I can only offer you, with sincere thanks for your kindness and complimentary call, my cordial coöperation in obtaining a man who can prudently go on a smaller salary than would be necessary for me.

With cordial regards, believe me,

Faithfully yours,

T. S. KING.

This letter contained one single paragraph

upon which we felt that we could hang a hope of success; and accordingly, by

return of mail, the Trustees dispatched to Dr. Bellows such documents as

removed from Mr. King’s mind all doubts as to his true duty. He accepted promptly—as promptly as he did everything

when convinced of the path in which he should tread. By an early mail, a

letter was received from Mr. Lambert, one of our Committee, enclosing a note to

him from Mr. King, as follows:—

BOSTON. January 2d, 1860

MY DEAR FRIEND: I hasten to say that I have written my resignation to the Hollis Street Parish, which will be offered this evening. To-morrow, I shall write to the Committee in San Francisco, so that the letter shall go by the mail of the 5th. Probably I shall stay there, if I live, two years. I have no time for further particulars this morning.

I hope I have made no mistake in deciding to go so far without going permanently. But trusting and praying that I may be of service to the noble brethren and the good cause in San Francisco, and pledging to you all my power to that end, during my stay there, I am, with cordial thanks for all your kindness, sincerely yours,

T. S. KING.

The following steamer brought Mr. King’s letter of acceptance—so noble, so frank, that it should ever be preserved in the archives of this Society as a memento of his goodness, and an enduring monument of his liberal, self-sacrificing spirit.

BOSTON, January 3d, 1860.

R. B. SWAIN, Chairman of Trustees

Of

Unitarian Parish San Francisco:

MY DEAR SIR: As I am now addressing you for the first time, in my reply to many kind and important communications, it is proper that I should explain to you my long silence. When your letters and documents of Nov. 3d reached me, I had just received a very urgent call to remove to Cincinnati, to take charge of a Society recently organized there. I had not anticipated such a response to my letter to Mr. Brooks, as your parish so generously returned. I supposed that the correspondence had ceased. Mr. Lambert was in quest of another minister for you, and as the movement in Cincinnati was backed by strong letters from prominent Unitarian clergymen, I found myself not a little embarrassed when your new call came, by the conflicting claims of your city, Cincinnati, and Boston. To add to my perplexity, I had engaged to lecture two weeks in December in the heart of New York State, which time was practically lost to me.

On Saturday last, December 31st, I made my decision to go to San Francisco, and on Sunday communicated it to my Society here. Yesterday I wrote a letter of resignation, which was read to a very full meeting of parishioners last evening. A large Committee was chosen to confer with me, and to ask me so to change the form of my withdrawal, as to accept leave of absence for fifteen months from the first of April, leaving it for the future to determine whether or not my connection with the Society should be finally dissolved.

The reasons for requesting this were: that the parish would be seriously shaken by an absolute withdrawal so suddenly; that I could not be sure of liking a residence in California more than a year; that my family might be anxious to return; that you might be dissatisfied with my service and prefer not to continue the arrangement; that if I should return so soon they would like to have the first claim to a resettlement; and that, if I should be wanted in San Francisco, and decide to remain longer with you, the devoted friends I leave in the Hollis Street Society could bear the separation better, if it should be gradually made.

The tone of the large meeting was so kindly—not a voice or vote dissenting—and the reasons for my leaving at all for California were so generously appreciated, that although the action of the parishioners was an entire surprise to me, I could not refuse assent to their request.

But I beg you to understand that I am not pledged or bound in the least, by the form in which the separation from Boston is made. I shall go to you with as much freedom as if I had never been settled in the East. Your generous guarantee offers me a salary for one, two, or three years, at my option. I accept the call for a year, to be your pastor during that period. If, before its close, I see clearly that I ought to remain longer, a letter to Boston, stating the fact, will release me from any obligation. And if, during that time, the Society here desire to engage another minister, nothing but a letter to me is needed to give them the moral right to do so.

I have been thus explicit that you may know it exact terms, and in detail, the state of the case. I ought to say, also, that Mr. Lambert wrote to me from New York, on December 28th, that it would be advisable for me to go, even if I should know beforehand that I could remain only a year.

But now, my dear sir, let me speak through you to the Trustees and the Society, unhampered by any details of business. I thank you most cordially for your strong and generous invitation. From the first moment when I received the call, last September, I was attracted to accept it for a time, that I might try and be of service in your fresh and promising field. My only regret is that any pecuniary questions have intruded to disturb the nobler considerations which should govern a clergyman’s choice. It was my necessities that dictated the particulars in the letter to Mr. Brooks, and I did not deem that the letter would be sent to your city. I shall go to you in hope of using all the powers that may be continued to me, for your permanent strength as a liberal Christian parish. My great ambition in life is, to serve the cause of Christianity as represented by the noblest souls of all the liberal Christian parties. I am not conscious of any gifts, either of thought or speech, that can make my presence with you so desirable as you seem to think; but, if I can be of service by coöperating with you, in laying deeper the foundations and lifting higher the walls of our faith in your city, whose civilization is weaving out of the most various, and in many respects the best threads of the American character, I shall have reason always to bless Providence for a rich privilege.

It is doubtful if I can leave here with my family before the 5th of April, but of this I shall know in a week or two; as soon as I can possibly go to you, you may be sure of my presence, and before we meet on the Pacific coast, let me ask you to accept a cordial general greeting, as brethren and friends, invoking for all of you health, prosperity, and every inward blessing of the perfect Providence.

In Christian bonds, your servant and friend,

TH. STARR KING.

Accompanying this letter was a private note to myself, a portion of which belongs to the history of the times.

BOSTON, January 3d, 1860.

MY DEAR MR. SWAIN: I sent yesterday my official answer to the generous call of your Society, with the reasons for its delay.

You will see that I shall hardly be able to leave before the 5th April. I have many lecture engagements to fulfill between this and March. I cannot relinquish them, for I shall need the money they will furnish to pay the expenses of removal and clear a few debts here. I am sorry that I am not in a condition to start at once.

May I ask you to inform me if there is a room that could be used as a minister’s writing-room in your church building.

I have not time to reply by this mail to the invitation of the Mercantile Library Association, but will do so in a few days. Of course I shall be glad to lecture for them at the time best suited to their convenience, and as to terms, will not fear that we shall disagree.

Cordially, yours T. S. KING.

This letter electrified the Society and gladdened the hearts of the community; for the fame of Mr. King, as a scholar and a divine, had long before reached this state of the continent, and the public rejoiced that a great addition was to be made to our stock of talent and energy. The future of our Society was no longer a question of doubt, and weeks before arrival of Mr. King, every pew in our church was taken, and we were at once placed upon a permanent and prosperous footing.

He left Boston on the 5th of April, 1860, but before his arrival several letters were received from him, from two of which I will make extracts.

BOSTON, March 4th, 1860.

MY DEAR FRIEND: Let me thank you cordially, though it must be hurriedly, for your kind and most interesting communications of the last mail. It gives me joy to learn that the tidings of the acceptance were so generously echoed. You seem to be anxious that I shall not doubt of the readiness of the Society to second all my labors and confirm my hopes.

Be assured, my friend, that I have no fringe or thread of skepticism on any such point. My only fear is lest you should be disappointed when I arrive, and find that your anticipations outrun any possible performance from me.

Would that I could have made arrangements to leave to-morrow. I had engaged my rooms in the Baltic for April 5th, and now she and the Atlantic are withdrawn. We must go in the Vanderbilt line, with prices raised to $200 a ticket. This is reasonable enough— but I should like to have had the advantage of the low fares, and especially of the better boats.

We cannot learn yet, either, whether or not April 5th will be one of the leaving days, under the new arrangement. Probably it will, but no advertisements are made, and no tickets sold so far ahead. We hope that the Northern Light will sail on that day. If I could have foreknown the present combination, you would see me, instead of this note, by the boat that takes this.

Dr. Bellows very kindly sent me your letter to him. I read its passages with practical interest. I expect to like California, and all of you, much better than you will return the feeling.

I am troubled in spirit a little as to our friend Buckingham. I hope that he can find preaching occupation that will be advantageous in the State, and shall be glad to assist him in any enterprise that will open such opportunity.

You can hardly appreciate the pressure on my time and thoughts of the last few weeks. A pile of letters now lies unanswered, for which I can get no leisure. This will account for my delay in relying formally to the Mercantile Library invitation. They can choose their own time for four lectures. Of course, I cannot hear from you in reply to this note. The next mail will probably gladden me with a communication from you.

I am, gratefully, your friend, T. S. KING.

BOSTON, March 19th, 1850.

MY DEAR FRIEND: I send a word by this steamer, although there is nothing of special moment that calls for a letter.

It has not been in my power to arrange for leaving earlier than April 5th. The Northern Light is announced for that date.

Next Sunday I am to preach my farewell sermon in Boston. The parish behave more nobly to me than I could have dreamed it possible. Their conduct, so large-minded and considerate, smooths my removal, while it attaches me still stronger to such friends by the heart fibres.

Drs. Bellows and Osgood have arranged for a public Unitarian breakfast party for me in New York the day before we sail. This is in honor of the faithful brethren in San Francisco, so I hope you will feel proud on April 4th.

In the hope of finding you well when I reach you and not quite sick of your bargain, I am, cordially, yours;

T. S. KING.

What followed upon his arrival is familiar to every person present. The Society grew in numbers, strength and enthusiasm. Mr. King at once ingratiated himself in the affections of the people. Answering a call from the Mercantile Library Association for a course of four lectures, he drew around him crowds, the like of which had never before been known in this city. Notwithstanding he was paid liberally by the Association, the lectures added largely to the treasury of that Institution, and he was invited to deliver a second course, which he was compelled to decline, from a sense of duty to this Society. What had been the history of our Church since then, is a matter of record. During the first year of his ministration, a debt of $20,000, which had been a halter about our necks, and which had threatened to strangle us, was extinguished. Not satisfied with this success, which surpassed the most sanguine expectations of the Society, he pursued his labors unremittingly. His active, ardent spirit knew no bounds, and he continued his efforts without any thoughts of self, but with an eye single to the best interests of those in whose cause he devoted the most of his time and talents. It soon became apparent that his field was too small, and that a larger church, more centrally located, was essentially necessary. To the erection of such a church, which should at once be an ornament to the city, an honor to the Society, and a true representative of our strength, he devoted all his energies. He started the call by a liberal subscription himself; he lent to the cause all the momentum of his sanguine, ardent nature; he enlisted others in its support by his example and his persuasive and convincing appeals. How well he succeeded for us, let this magnificent edifice, so beautiful, so tasteful, so grand, attest. What was the result to himself, let that grace answer. For I solemnly believe, that to his devoted care and anxiety and toil in the erection of this building, may be attributed much of that physical debility which undermined his constitution and shortened his days. He gave us the church with his life. He gave us a temple, elegant in its proportions, ample its accommodations, and pleasing to the taste and refinement of the people. But the organ he so liberally donated to the Society was used to sound his requiem, the pulpit he adorned is his mausoleum, and the Church is his own enduring monument, consecrated forever to the memory of his goodness, his affection to his Society, and his undying name.

Mr. King, as if possessed of the gift of prescience, had long entertained the belief that he would never reach the age of forty. He said but little upon the subject—but a short time after his arrival here, he addressed an interesting communication to me upon the affairs of the Church, in which this idea was constantly interwoven. It appeared as if it were his desire to place his impressions upon record—and so strong were these feelings, that he was the more anxious to put the affairs of the Church upon a safe foundation immediately, and complete the work which he had begun. Some who did not know him, attributed this anxiety to a determination on his part to leave the State at an early day. I am sure he had no intention of leaving us permanently. A few months ago, he unfolded to me all his plans, and he then stated that he was desirous of visiting Europe, and particularly Germany, for purposes of education; that if he could leave here for a period of two years, for travel abroad, and improve his mind and health, he would be glad to return and remain. If the Liberal Christian thought best to build him another and smaller Church, he would be quite content to preach. If not, and they were satisfied with the minister who should be installed during his absence, he would devote himself to literary pursuits, to preaching occasionally, and to advancing our cause and the cause of public charities throughout the State. But I must read the letter to which I have alluded.

SAN FRANCISCO, August 16th, 1860.

MY DEAR MR. SWAIN: I have thought very seriously since Tuesday evening, of the objects and results of the meeting of the Trustees at my house, and I venture to trouble you with some lines, which had better be written than spoken.

I regret to learn that the debt remaining against the parish is so large as $8,000, and I cannot help feeling some serious concern in relation to it. My special object in sending you this note is to learn if any way can be opened by me that will lead to the liquidation of it, or a large portion of it, this fall.

What moves me more powerfully,

is the apprehension I have begun to feel as to my health.

Six or eight months before leaving Boston, I began to be conscious that my health was insecure. I could not bear the thought of a long season of invalid-ism, and a long experience of lying-upon-the-shelf-itiveness; and so I was more strongly impelled to California, by the hope and belief that I could help the brethren and the cause here by labor that would not exhaust my lessened strength, while the climate would repair the damage, and possibly fill the fountain with an unusual store of vitality.

It is useless for me to shut my eyes to the fact that I am not so well as I was when in Boston. I experience strange debility, and singular pains and numbness in the brain. For writing purposes I am nearly worthless—and the symptoms are the more serious from the fact, that my father’s constitution (which in most respects I seem to have inherited) snapped at about thirty-six. He was a very strong man till then, but broke thus early, was good for nothing for three or four years, and died at forty-one.

Now, I desire to be of essential service to the parish here, by my visit. I cannot be unless your debt is wiped out. If I shall not grow stronger this fall and winter I must return East next spring, to stop all ministerial work—perhaps, to cease all work on this planet—and it would be a very bad thing to leave you then, with four or five thousand dollars of debt to be paid.

Can I not, think you, start some plan for paying off so large a portion of it this fall, that there will certainly be none remaining next spring? Then you would be on the safe side; and if my health should improve, and I can stay with you longer, another period of service would bear the more fruit. Would any proposition from me, in a sermon, towards such a result, be out of place? Of course, I should breathe no word of my real motive, as to my state of health. I do not wish you to mention it. I have not even told my wife these fears, and she does not know that I write this letter. Yet I am so impressed with the suspicion that my constitution is impaired, that I feel it my duty to consult with some one as to this matter of the debt, and the future of the parish—and with whom so properly as with you?

Do not allow yourself to be worried, or even seriously alarmed, by what I say. Look at my fears, as I do for the present, in a business light, and tell me what can be done, and how best done to put the parish out of danger. I am perfectly willing to take the matter out of the Trustees’ hands, if you say so, and try my luck from the pulpit in reducing the debt.

In everything I say about my strength, I am understating rather than overstating. Some days I do not seem to have a thimble-full of vitality; but with what I have, I am wholly your friend,

T. S. KING.

P. S. —Do not reply to this by pen; we can talk as well.

I seized an early opportunity to have an interview upon the subject of the letter. His thoughts were altogether with reference to the prosperity of the Society, and the danger of his breaking down, and leaving us to carry the heavy burden of debt. I endeavored to dispel his fears in regard to his health, and inquired why such a presentiment had possessed him. He said it was no presentiment, but an inwrought conviction; that the conviction was well based on physiological grounds; that he entertained no fears of death; that but for his anxiety in regard to his family, he could hail the approach of death with pleasure; that his life had been one of great toil from his earliest boyhood; that he had looked forward to each approaching year as a season when rest would be vouchsafed to him, but it never came. Every year brought new cares, new responsibilities, new labors, and he had come to the conclusion that there was to be no rest for him on this globe. He again said, that but for his anxiety for his family, he would, therefore, be glad to enjoy the perpetual rest which could only be found beyond the grave.

Mr. King’s labors were immense. He never lost a moment. He knew how to economize time. But his time was much broken by constant demands upon his charity and kindness. Every claimant found a respectful audience, however pressing his duties, and no deserving one was turned away unsatisfied. His charities were entirely unostentatious, and oftentimes stealthily bestowed; so stealthily that not even the members of his own household, nor his friends were informed of them. I am sure that he took a secret delight in unheralded acts of kindness, and that he found sufficient commendation in the silent approval of his own heart. One of our own parishioners has informed me, since his death, that he has been paid hundreds of dollars by Mr. King for wood that he has ordered for suffering families—and another has also stated to me that he had sent large quantities of the necessities of life, such as flour, sugar, etc., to different sections of the city, by direction of Mr. King, for the poor and needy. These quiet deeds of charity had a peculiar charm to him. But he was discreet in the bestowal of his favors. I know that Mr. King took much time to inquire into the merits of each case, and that he was seldom deceived. He took a broad view of suffering. When cases were presented to him, the sufferer urged of course only the selfish side. Mr. King saw all around and through it, and took an intellectual as well as a Christian view. The sufferer might seek to obtain relief from immediate wants—Mr. King thought of his degradation, of his wounded pride, the poverty-stricken spirit, and what might be his usefulness to society if raised from the “Slough of Despond” to a position of prosperity. And so he gauged the extent of his charities, for he seldom stopped to reflect upon the amplitude of his own purse.

By reason of these constant drafts upon Mr. King’s attention, the execution of some of his most important labors were impeded and sadly interrupted. While the rest of the world was enjoying the repose of sleep, he was laboring. He was compelled to use the midnight hours for much of his literary work, and I have frequently known him to finish his morning sermon fifteen minutes before the church services commenced. His most eloquent perorations have been written, watch in hand, but a few minutes previous to the delivery of the exordiums.

In spite of these perpetual claims upon his time he was, nevertheless, a thorough student; not a library in San Francisco, of any note, either public or private, that he had not consulted. His perceptions were so active, his intuitions so keen, and his memory so retentive, that he understood, appreciated, and learned instantly. He never ceased to study. Circumstances prevented him from completing his college course, but he none the less qualified himself for his degrees, which were bestowed upon him, without solicitation, by Harvard University.

One of the newspaper writers says that “Mr. King’s” scholarship was not deep, nor extensive, not even in theology.” And another says: “Not favored with college or university advantages, he was thoroughly and carefully read in the literature of his own language.” These writers evidently did not know whereof they affirmed. They have imbibed the error common to college graduates, of supposing that a man without an Alma Mater cannot be a scholar. Mr. King was so much the more deep and profound in his scholarship. He had no college education to fall back upon, but he continued his researches until he died. He was thoroughly conversant with the Greek, Latin and Hebrew languages, and understood well the French and German. But he hated pedantry. He never obtruded his knowledge upon the observation of others, and in conversation or public speech, seldom, if ever, quoted from the classics.

No one who remembers his famous controversy, a few years since, with a distinguished divine and an apostate from the Unitarian faith, in Boston, dare doubt his scholarship. No one who knew him intimately will deny that he had mastered several of the modern languages. In the case of the controversy to which I have alluded, a question arose as to the correct translation in the English Bible of certain passages from the Greek and Hebrew. His antagonist, than whom, it was supposed, no riper scholar lived in Boston, under-estimated entirely the powers of his opponent. So completely did Mr. King annihilate him, that he sought the editor of the paper in which the argument was conducted, on Sunday; confessed his error, and implored him, with tears in his eyes, to spare him.

His acquaintance with the French language was perfect. He never used a translation when he could procure the original; and as to the depth of theology, those may safely question it who never crossed swords or measured lances with him. Probably a more thoroughly learned Biblical scholar never entered a pulpit. And yet, Mr. King was modest in his pretensions; he underrated himself; his humility was so great, that he never correctly appreciated his own abilities. If he was praised, he thought himself undeserving; if blamed, or severely criticised, (sic) he was ready to believe that he was justly open to criticism or censure. Singular as the statement may seem to many here, he was extremely sensitive to praise or blame; he enjoyed the first less, and suffered from the second more, than most mortals.

Although Mr. King preferred to labor in the field of literature, for which his tastes and habits best adapted him, his sympathies for humanity were so broad, his love of country so intense, and his patriotism so ardent, that upon the breaking out of the rebellion he at once arrayed himself against treason and traitors. At a time when all the people were stunned by the development of the designs of the enemies of our country, Mr. King commenced to exhort from the pulpit and the forum. He rose to the majesty of the occasion. His eloquence was never more fervent, never more convincing. The position to be taken by California among the States, always exercised political and social control. Now it became rampant. Loyalty was only a latent, not an active sentiment. It was uncertain whether Unionism, a Pacific Republic, or Secessionism would prevail. The masses were undecided and wanted a leader. At this critical moment, and as if by the direct interposition of the Almighty, Mr. King stepped into the breach and became the champion of his country. Taking the Constitution and Washington for is texts, he went forth appealing their duty. They had been waiting to be told what course to pursue. He at once directed and controlled public sentiment. He lost no opportunity to strike a blow at the rebellion. Visiting different sections of the State, he kindled the fires of patriotism wherever he went, by his matchless eloquence and unanswerable arguments.

Not the least of Mr. King’s efforts were his labors in the cause of the United States Sanitary Commission. He early understood and appreciated the vast good which that organization was capable of doing. He considered it the grandest and most magnificent scheme of charity the world had ever known, and he labored faithfully to promote its interests. Conceiving that the isolation of California had deprived the people of the State of the opportunity of assisting the Government in the suppression of the rebellion, he thought that no better channel could be afforded to loyal citizens to manifest their money to the Treasury of the Commission. Who does not remember his magnetic speeches in Platt’s Hall, and the liberality with which the people, within a few days, poured out their hundreds of thousands? For the purpose of keeping loyalty alive, and also for the purpose of advancing the cause of the Commission, he traveled through nearly every section of the State. He visited Oregon, Nevada and Washington Territories, and even extended his journey to Vancouver. Wherever he went his influence was felt, and the people liberally and willingly poured their money into the Treasury of that organization. I would not detract from the generous and well-timed efforts of those self-sacrificing gentlemen who coöperated with him in his herculean labors, but I exaggerate nothing when I say, that to him, more than to all others, is due the glory of contributing so princely an amount to the Treasury of the Commission, that California now stands foremost in the sisterhood of States, upon the score of generosity. He was just preparing another campaign in the interior, when he was stricken ill.

I have a large correspondence from him, written while engaged in his patriotic travels. When absent from the city, and relieved of the cares incident to the life of a clergyman, he seemed to be particularly happy. He would derive inspiration from nature. His spirits, always cheerful, were on such occasions, exuberant, and oftentimes rollicking. Although the tone of the letters I now propose to present does not exactly accord with the sadness that now pervades this congregation, I cannot refrain from reading some of them here. They present a phase of the character of our dear pastor, which you have all enjoyed, and which was one element through which he reached the heart of the people. His genial disposition, his love of humor, and his passionate fondness of Nature, never failed to shine brightly when engaged in correspondence.

Early in 1861, he traveled through the northern part of the State, delivering patriotic lectures. From Yreka he wrote me as follows:—

YREKA, May 29th, 1861.

Here I am, perched on the top of the State, where I can almost toss a copper or a “five-cent piece” over to the Yankees in Oregon—but I shan’t try it, for fear of corrupting their Union principles.

My health is very good. The journey has been quite fatiguing. From Shasta to Yreka we were twenty-seven hours on the road, and I had an outside seat day and night without a shawl. But I am all right, and my brain has settled again right side up, I believe.

The weather was very cloudy from Monday, when I started, till last Sunday. Then from Shasta town I caught the first view of Shasta Butte; it was just after sunrise, and the view was glorious indeed. I preached after the vision for a Methodist minister, and ought to have preached well; but am afraid I didn’t.

To-night I am to speak in a village with the sweet name of “Dead Wood,” and to-morrow I shall dine and sleep at your brother’s, in Scotts Valley, and speak in the evening at the very important and cultivated settlement of “Rough and Ready.” “Scott’s Bar” wants me. “Horsetown” is after me. “Mugginsville,” bids high. “Oro Fino,” applies with a long petition of names. “Mad Mule” has not yet sent in a request, nor “Piety Hill,” nor “Modesty Gulch” but doubtless they will be heard from in due time. The Union sentiment is strong, but the secessionists are watchful and not in despair.

Yesterday I devoted to a study of Mt. Shasta. I had it in view for ten hours, and sucked it in as an anaconda does a calf. It is glorious beyond expression—it far exceeds my conception of its probable grandeur. I am glad that I called my book the “White Hills.” To-day is very cloudy, and this mountain is shrouded to the base. Yesterday was the first perfect day that has been here in a fortnight, so I was truly favored. You should by all means see Shasta, and the Scott Valley, where your brothers live. The whole region is sublime. I shall have lots to report to you on my return. I hope your preaching has been good and well attended.

With cordial regards, believe me sincerely yours,

T. S. KING.

The following year he again visited the northern part of the State. During the journey, he frequently addressed me. I will read one characteristic letter. YREKA, July 21st, 1862.

I have received your telegram to-day, for which, except your paying for it, please accept my thanks. I ordered the word to be sent to you—“Answer paid here.” If you received it and still paid, you did a mean thing, which can’t be settled till I return.

It is quite hot here to-day, but as it is not 100° no-body calls it hot; anywhere in the nineties, even 99° is moderate—a hundred is hot. We rode all night of Saturday through from Shasta here, making the trip in twenty-eight hours. The journey from here will be terribly hard, and I almost regret that I made the overland trial. From Jacksonville, where we go to-morrow, to Salem, will be as tough as it can be—it will take three or four days. I doubt if I shall have time to see all I wish to of Oregon and Puget Sound. It will take me another week to reach Portland, and I begin to fear that I shall have to abandon the whole Puget Sound and Victoria expedition. And the expenses are simply frightful—it cost me over eighty dollars for passage from Marysville to Shasta town, and if I travel through part of Oregon by extras, as I must, sixty dollars a day will be the lowest I can do it for, and I have purchased through tickets besides.

We have seen Mt. Shasta to-day. He is splendid, but not so glorious as last year, for he has not so much snow as then; but it is a magnificent sight indeed. I shall drive out again at sunset to see him, and then come in to lecture here once more. In spite of secession and Greathouse they will have a lecture again. I didn’t wish to, and am sorry that I consented.

I hope the church plans are finished, and the working near at hand. Good word to everybody. From your friend. T. S. KING.

P.S. — tell W. M. that it lifted a load from me to learn that his father is brighter. Give my sympathy and greeting to the good Captain. T. S. K.

His last expedition to the country appeared to invigorate him more than ever. His spirits ran unusually exultant.

LAKE BIGLER, June 5th, 1863.

I arrived here this forenoon, about ten o’clock. The stage ride from Folsom to Placerville was very hard; but we took an extra from Placerville on and found it delightful. The scenery is nobler than I anticipated, and the situation of the Lake is certainly one of the wonders and masterpieces of scenery belonging to our insignificant little globe. It is of no use to attempt to describe it—I will tell you about it when I return. There should be a law compelling all Californians to visit the Lake on pain of—being transported to the East. It will be a great benefit to me, I am sure, to breathe the keen invigorating air for a few days, eat trout by the hundred weight, hear the roar of the wind through the noble pines, and look at the abundant snow on the superb peaks over the inland sea. I don’t feel as though I ever had a head—and this in two or three hours.

Yours, sincerely, T. S. K.

I will cut extracts from one more letter written while on this tour, which illustrates not only his exultation of spirits when relieved of professional duties, but also how his best thoughts were always of his parish.

LAKE TAHOE, June 25th, 1863.

Ever since Eve ate the apple, clothing has been necessary to the human race, and J. C. M. (admirable man) became an indispensable element in civilization. I wore my best clothes in Nevada, and my extreme hope now is to induce them to hold together till I can get back. But if I address the citizens Fourth of July, I must be decently clad. So for a commission for J. C. M. If he has my measure, let him make me at once a coat, vest and pants—black. I would like to have the coat a leetle larger than the former one, which was a little too short in the waist and tightish under the arms. It fitted too well. I hate to have a man give me fits. When a secessionists comes in, let M. do his best in that line. If Mr. M. can make the clothes to be ready on the morning of July Fourth, and will make them first rate, I will wear a placard during the delivery of the oration: “Buy all your clothes of J. C. M., one of the best men on the Pacific.” Will you carry the message to him at once?

The weather is glorious here. A friend went out before sunrise and caught four large trout, one of which I ate for breakfast. I have received a noble hymn from Bartol for the dedication of the church.

I feel ashamed not to be home for next Sunday, yet cannot help feeling that it is wise to stay. The next four months will try my constitution more than any similar period of my life, and I believe the entire rest here will be profit to the parish.

Tell Georgie there are three young eagles here which were taken from nest in a high tree last week. They have great claws and splendid eyes. How he would like to see them! and I wish he could, but I am afraid he would stick his sharp bill through the paper before reaching Sutter street.

Your friend always, T. S. KING.

I have no doubt that his constant studies and his anxieties and unrest here undermined his constitution, and, as the resolutions say, precipitated his death. I can never forget the last time I saw him out of his own house, the Friday before he died. He appeared much depressed in spirits—complained of aching bones and a sore throat, and said that he felt like a sponge squeezed dry. Not being well, he was particularly sensitive that day—was unusually thoughtful and sad. When we parted, he expressed a fear that he would not be able to preach on Sundays, and felt deep regret at the thought, for he had made considerable preparation for the vesper service, which he declared would be the richest of all; and then, he said, he had several important notices to give—particularly the one in regard to the social gatherings on Wednesday, in which he took so deep an interest, and of the success of which he was so very proud. “But,” said he, as we separated, “come around in the morning, before you go down.” He returned to his home never to leave it, save when his spirit took its flight to regions beyond the stars. Morning came, and Mr. King was perceptibly worse. He had changed materially, and I saw that he was a sick man. I did not, however, appreciate the extent of his illness until the following evening— Saturday. He had invited two or three friends to his house to take a cup of tea and pass the evening. Finding himself unable to be personally present, he sent to me the request that I would join them at the table. I knew that Mr. King must indeed be very feeble to deprive himself of the pleasure of the society of his own invited guests—and he was feeble. While we were at supper, a bridal party came unexpectedly. Here his spirit of self-sacrifice shone out resplendently, for although he was too much prostrated to see his personal friends, he yielded to the urgent solicitations of those strangers, who he begged would excuse him; arose from what proved to be the bed of death, dressed himself and came down the stairs to perform the marriage ceremony.

The wedding ought to be doubly sanctified to the bride and groom for the heroic spirit of kindness and generosity which prompted him, under such circumstances, to perform the ceremony—the last professional act of his life.

After the ceremony, we met in the hall. He looked wretchedly. He was on his way to his bed, from which he was never to rise. Still he was cheerful, expressed his regret that he could not remain longer with his friends, and indulged in a few pleasantries before leaving.

From that time the disease “crept on with slow and steady pace.” On Wednesday, his physician, in view of the great value of his life to his family and the country, advised with some of his friends as to propriety of a consultation. It was then apparent that Mr. King’s life was in danger. On Thursday, there seemed to be a change for the better, and it was evident the disease mastered; but he was suffering from great physical prostration and exhaustion of the vital energies. If the usual tone of his system could be restored and strength given him, there would be no doubt of his recovery. But this was not to be. That evening, alarming symptoms manifested themselves. He rallied, however, and passed a tolerably comfortable night, sleeping well and breathing with comparative ease. We were all much encouraged, and believed the worst was passed. It was only the calm that precedes the storm—a lull in the fury of the disease preparatory to a last desperate onset. For, on Friday morning, just before six o’clock, while I was standing by the bed-side with the physician, who also had been with him all night, a perceptible change took place in his appearance which told too plainly that the time for parting had come—that the angel of death was there, and that our dearly loved pastor and friend would soon pass “beyond the sightless verge of this land of tombs.”

The scene that then followed no pen can describe—no imagination can conceive. Mr. King had achieved many triumphs for us by his toil and genius. The time had now come for him to achieve the crowning triumph of all—a triumph of his religion—a triumph over death, and a vindication of his life and character.

Dr. Eckel approached the bedside for the purpose of informing him that he could not long survive. But Mr. King, who had watched the progress of his disease with all the precision of a scientific observer, and all the coolness of a disinterested spectator, though not without solicitude, had discovered the change, and anticipated him by inquiring as to the character of this new symptom, and whether he could survive it. When told that he could not, there was not the slightest evidence of agitation. He calmly and inquiringly looked in the doctor’s face, and asked how long he thought he could live; as if he desired to know as nearly as possible how much time was allowed him on earth to make the necessary preparation. When told but a half an hour, he immediately replied, “I wish to make my will.” Remembering that he had told me at some time that he had left a will in Boston, I answered, “Have you not a will already, Mr. King?” He promptly replied that his “little boy was not then born.”

Some little time was consumed in preparing to write by his bed-side, during which he appeared to be sinking rapidly. I feared his life would not be spared until he could sign the document. But when the preparations were made, the power of his will became manifest. Then commenced a desperate struggle to sustain life until his temporal arrangements were completed; for although he had not been able to speak louder than a whisper, he now, by a strong effort, raised his voice to nearly its ordinary pitch, and clearly and forcibly enunciated his wishes, saying no more than was necessary, and leaving unsaid nothing. Having finished this task, he seemed to be much exhausted. I approached his bed-side with the will in my hand, that it might be read to him previous to signature. He had then apparently relapsed into a comatose state. I said, “Mr. King, can you hear me? He opened his eyes with a smile and said, “Read on.” Turning his head slightly, in order to catch every word, he answered, at the end of each paragraph, “all right.” And when the reading was concluded, and he was asked if anything more was to be added, he replied, “No, it is just as I want it.” Waiting a moment as if in thought, he then said, “Add that all other wills are hereby revoked; you know I have another will in Boston.” We who had not death staring us in the face, had failed to detect this omission of so vital a clause. He was more calm than any of us. He was raised in bed, in order that he might sign the document. With a book for his desk, he took the pen with a steady hand, deliberately dipped it in the ink, and, to the astonishment of all around, wrote his name (which even a well man could not easily write surrounded by such difficulties) with a firmness and rapidity and case not surpassed even by himself. He looked carefully at the signature when finished, punctuated it as usual, reached the pen to one who was standing by, and “laid him down to die.”